|

The

News

News

Dedicated to Austrian-Hungarian Burgenland Family History |

THE BURGENLAND BUNCH NEWS - No. 259

September 30, 2015, © 2015 by The Burgenland Bunch

All rights reserved. Permission to copy excerpts granted if credit is provided.

Editor: Thomas Steichen (email: tj.steichen@comcast.net)

Archives at: BB Newsletter Index

Our 19th Year. The Burgenland Bunch Newsletter is issued monthly online. It was founded by Gerald Berghold (who retired from

the BB in the Summer of 2008 and died in August 2008).

|

Current Status Of The BB:

* Members: 2374 * Surname Entries: 7665 * Query Board Entries: 5479 * Staff Members: 17

|

This newsletter concerns:

1) THE PRESIDENT'S CORNER

2) A HUNGARIAN WEDDING INVITATION

3) RESEARCHING MY HAIDER ANCESTRY (by Cheryl Richardson)

4) TUTORIAL III: 1720 AND 1715 URBÁRS

5) CROSS-REFERENCE OF URBÁRIAL VILLAGE NAMES

6) HISTORICAL BB NEWSLETTER ARTICLES:

- LUTHERAN ORIGINS IN SOUTHERN BURGENLAND (from Fritz Königshofer)

7) ETHNIC EVENTS

8) BURGENLAND EMIGRANT OBITUARIES (courtesy of Bob Strauch)

|

1) THE PRESIDENT'S CORNER (by Tom Steichen)

Concerning

this newsletter, after the bits and pieces here in my "Corner," Article 2 is an article about a Hungarian Wedding

Invitation. Truly, it is not often that I get to write about the softer and gentler side of the European life our

emigrant ancestors left behind, about the nice things like formal wedding invitations. It is my hope that this story will

help round out the picture I try to paint about their time and place. Concerning

this newsletter, after the bits and pieces here in my "Corner," Article 2 is an article about a Hungarian Wedding

Invitation. Truly, it is not often that I get to write about the softer and gentler side of the European life our

emigrant ancestors left behind, about the nice things like formal wedding invitations. It is my hope that this story will

help round out the picture I try to paint about their time and place.

Articles 3, by Cheryl Richardson, is a combination trip report and ancestor hunt, complete with a surprising

twist! But I'll let Cheryl tell you about that in her story about Researching Her Haider Ancestry.

Article 4 is a third Tutorial article related to the resources found on the Hungaricana website.

This time, however, it is about the 1720 and 1715 Urbárs, which, while accessible from the Hungaricana

website, are more accessible via direct links on the BB website.

In Article 5, I provide a (large) Cross-Reference table that relates the current Burgenland

village names with the Urbárial Village Names as listed in the 1715, 1720 and 1767 Urbárs. There are a

few "bonuses" included too... but you will need to read the article to learn about these.

The remaining articles are our standard sections: Historical Newsletter Articles, and the Ethnic

Events and Emigrant Obituaries sections.

New Hungarian Translator: Last month I reported the passing of Joe Jarfas, calling him "one of my go-to

correspondents when I needed to understand something 'Hungarian' or needed to translate an obtuse official Hungarian

document." Over the years, Joe had become a friend, and it is the loss of that friend that I mourn most of all. However,

as BB Newsletter Editor, I also lost a valuable resource, and I worried about replacing that capability.

Enter Réka Kieß! Réka became a BB member in April 2014, being interested in the Hirsch surname from

Stöttera and Rohrbach (bei Mattersburg) and the Kiesz surname (possibly from Donnerskirchen). We were able to provide

her some leads on her families.

She has since made the occasional comment on newsletter articles, including a comment on last month's Szolgálati

Cselédkönyv article. In that comment, she also said, "Should any of the members abroad need some help in the future

with Hungarian translation, please do not hesitate to provide them with my email address. I would be happy to help as I know

myself how difficult it is at times to understand complex sentences that dictionaries are not useful for."

What else could I say but "Thank you, Réka, for your kind offer to assist!" So I did... and I quickly enlisted her as

my resource for Hungarian transcription, translation and more.

When

I first conversed with Réka a year and a half ago, she was in Budapest working both as an English tutor and for the

National Archives of Hungary. When

I first conversed with Réka a year and a half ago, she was in Budapest working both as an English tutor and for the

National Archives of Hungary.

Born in Budapest, she completed an undergraduate degree in English Language and Linguistics at the Károli Gáspár

University of the Reformed Church in Budapest in 2002 and then obtained a Cambridge CELTA Certificate (certifying

skill in teaching English to speakers of other languages). She next studied Publishing at the Donau Universitat.

Just this year, she completed a post-graduate degree in the field of Rare Books and Manuscripts Librarian at the

University of Szeged. One aspect of this degree is expertise in paleography, which Wikipedia tells me is "the

study of ancient and historical handwriting.... Included in the discipline is the practice of deciphering, reading, and

dating historical manuscripts, and the cultural context of writing.... The discipline is important to understanding,

authenticating, and dating ancient texts."

Along the way, she has worked in archives in Europe, acted as proofreader and lector for various science papers and

publications, and became actively involved in linguistic research into the language of printers and publishers in Hungary,

England, France, Germany, and Italy. She is currently researching the evolution of the language of printers and loan word

etymology in the above mentioned languages.

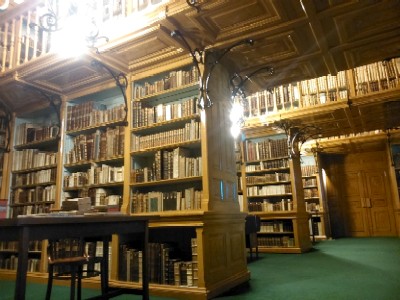

Since

August, she is a "rare books and manuscripts research librarian" working in the Somogyi Károly Regional Library

in Szeged, particularly in the special collection of the Somogyi Foundation, where incunabula (books produced

before 1501 from movable type), and other old books and manuscripts are kept. Since

August, she is a "rare books and manuscripts research librarian" working in the Somogyi Károly Regional Library

in Szeged, particularly in the special collection of the Somogyi Foundation, where incunabula (books produced

before 1501 from movable type), and other old books and manuscripts are kept.

She also tells me that she maintains relations with colleagues in the National Archives and is closely connected to

the regional archives in the county of Csongrád, also a part of the National Archives.

As you might expect, this extensive educational background, along with her Hungarian origins and her English communication

skills, should allow her to be of tremendous help in reading, transcribing and translating old Hungarian handwriting. I look

forward to a long successful collaboration with her!

Not So Good News From Eisenstadt: Recently, I asked Klaus Gerger to try to get the current status of the

church records (matrikels) digitization project of the Eisenstadt Diocese. He did and, as the title of this tidbit

says, the news is not good. Klaus visited the Archive to speak with the head archivist, Mr. Weinhäusel, and he

learned the following:

First,

the digitization project is stopped due to the limited budget. As I had noted previously, a significant number of

the church books were in poor condition. Thus a decision was made to dedicate the currently available money to

restoration of books only. While this does not help us internet researchers immediately, it does mean the books will not

be lost to decay, will be available in the Diocese Archives for onsite research, and maybe can be digitized in the future. First,

the digitization project is stopped due to the limited budget. As I had noted previously, a significant number of

the church books were in poor condition. Thus a decision was made to dedicate the currently available money to

restoration of books only. While this does not help us internet researchers immediately, it does mean the books will not

be lost to decay, will be available in the Diocese Archives for onsite research, and maybe can be digitized in the future.

Second, Herr Weinhäusel assured Klaus that onsite researchers are very welcome (though an

advance appointment is mandatory). However, he also said that, while the staff of the Archive will not do research,

they will provide scans of single pages (via mail) if precise access data (date and name) is provided and

staff time is available.

Third, Herr Weinhäusel recommended Felix Gundacker as a professional genealogist for paid research.

Nickelsdorf Takes Center Stage: BB Contributing Editor Frank Paukowits comments on the refugee

situation in Europe...

It’s

a town of 1,600 inhabitants in the Neusiedl District of Burgenland but, most recently, Nickelsdorf has become the passageway

for tens of thousands of refugees streaming through Eastern Europe to find better lives in the West. While Germany, by far,

is the country which has agreed to provide sanctuary to the largest number of refugees, the Austrians have demonstrated

concern over the plight of these people. In fact, newspaper reports recounted how refugees began clapping when they had

realized they had reached the Austrian border. It’s

a town of 1,600 inhabitants in the Neusiedl District of Burgenland but, most recently, Nickelsdorf has become the passageway

for tens of thousands of refugees streaming through Eastern Europe to find better lives in the West. While Germany, by far,

is the country which has agreed to provide sanctuary to the largest number of refugees, the Austrians have demonstrated

concern over the plight of these people. In fact, newspaper reports recounted how refugees began clapping when they had

realized they had reached the Austrian border.

The people come from places like Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and areas in Africa that have been ravaged by war for many years.

They are desperate and have traveled by boat and foot across countries like Turkey, Greece, Hungary Serbia, etc., to find

refuge in countries that have demonstrated a willingness to provide a place to live and humanitarian relief.

This situation is reminiscent of the plight of my own ancestors who fled Croatia 500 years ago while being pursued by the

Ottoman Turks. These people resettled at that time throughout Burgenland and became an integral part of the German/Hungarian

towns in the area. Personally, I am glad that there was a haven for my ancestors many years ago.

Ed:

Frank is correct that Nickelsdorf, Burgenland, being the first train station over the border from Hungary, has been the

primary access point for refugees entering Austria from Hungary. Temporary accommodation centers (see example to the right)

have been created to feed and house the refugees as they wait for further transport into Europe. Similar facilities are in

Parndorf (the village nearest the infamous abandoned truck) and other nearby areas. My understanding is that Burgenland has

offered permanent asylum for about 3000 refugees but only a handful have chosen, so far, to seek asylum there. Ed:

Frank is correct that Nickelsdorf, Burgenland, being the first train station over the border from Hungary, has been the

primary access point for refugees entering Austria from Hungary. Temporary accommodation centers (see example to the right)

have been created to feed and house the refugees as they wait for further transport into Europe. Similar facilities are in

Parndorf (the village nearest the infamous abandoned truck) and other nearby areas. My understanding is that Burgenland has

offered permanent asylum for about 3000 refugees but only a handful have chosen, so far, to seek asylum there.

DNA Cousins (follow-up): Last month I commented on Richard Potetz' reported autosomal DNA "ethnic makeup"

included 3% "Asia Minor" (per FTDNA) or 0.4% "East Asian" (per 23&Me) and my own 10% "Asia

Minor" component. I light-heartedly argued that, thus, our ancestral background possibly included a little "Ottoman

Turk" DNA, compliments of the Ottoman armies that roamed Burgenland in the 15 and 16 hundreds.

This prompted Bob Schatz to write, saying (in part):

I thought to send a quick note re your mention of Asia Minor DNA in your and Richard Potetz' autosomal makeup. I

hate to dispel any notions of 15th-16th century Ottoman Turks or Burgenland slaves, but this part of your DNA could

reflect a much more distant Neolithic connection.

Like you, many people of Central and Southern European extraction have some percentage of Asia Minor or East

Asian DNA (I myself have 25% through my father, with close matches to men currently living in Italy and distant

matches to men currently living in Turkey and the Levant). Anthropologists believe that the presence of "Asia

Minor/East Asia" genes in the European population represents a demic diffusion from that part of the world to

the western Mediterranean, occurring at various times either in pre- or recorded history through trade, settlement, or

military recruitment.

When discussing DNA, we need to take into account that "ethnic makeup" is often a cultural veneer over our deeper biology.

In the case of current matches living in Turkey, it's good to keep in mind that although the culture of Asia Minor is now

Turkish, the population of Turkey is not all "Turkic" biologically / genetically. History shows that while

there was always movement of peoples, general populations tended to stay in place over long periods, and the cultures of

those populations shifted as their ruling elites replaced each other through conquest or economic advantage (Central

European Celts becoming Germans or Slavs, for example).

In their long history, the peoples of Asia Minor have lived through many cultures, Turkish, of course, being just

the most recent. The ethnic designations used in autosomal testing usually refer to the place or the culture that was in

existence when a particular genetic mutation occurred, so for example we shouldn't extrapolate forward that the

presence of "Asia Minor" genes automatically = a "Turkish" ancestor.

In Richard's case, it would be best to determine how far back in time he shares a common genetic ancestor with his Turkish

match (the age of the shared genetic mutation). If that ancestor, or rather the shared genetic mutation, falls within the

Modern Era (1500-present), then indeed it could very well point to an Ottoman.

I thank Bob for reminding me to think a little deeper on the meaning of these "place" (rather than "ethnic") designations...

with that in mind, I herewith quote the "Primary Population Cluster Description" that FTDNA provides for the "Asia

Minor" designation:

The Asia Minor group is present from South Asia, Turkey, the Caucasus, and along the shores of the

Mediterranean Sea. It was home to early hunter-gatherers and farmers. It has a deep history and connects to many lineages.

It is the mark of those who moved east to west and back again, along what would become the Silk Road. The Asia Minor group

is connected to the oldest groups of modern humans. As early humans left Africa, they settled in this area. The

hunter-gatherers were eventually replaced by the first farmers.

Early recorded history confirms several cultures lived in this area and left their mark, such as the Phrygians, the

Hurrians, the Hittites, the Hatti, and the Armenians. Later, the Turks swept down from Asia and brought people from the

Asian Northeast group. Likewise, the Arab expansion brought members of the Eastern Middle East group to the southern

borders of the Asia Minor. We find that it is the strongest in Turks from the Fertile Crescent and people from the

Caucasus. Closed social groups, such as the Druze and Assyrians, also have clear signatures of the Asia Minor group,

suggesting that their genes are native to the region.

Thus we see that, as Bob suggests, there are many "ethnic" groups that fall under the "Asia Minor" designation, with

Ottoman Turk being one such group. The territory of the modern state of Turkey (and that of surrounding states) has

been under the historical political rule of many empires, each of which changed the local culture and influenced the

"ethnic" genetic makeup of the region. The Ottomans only arose in 1299 AD, establishing Constantinople as its capital

in 1453. Prior to that, the region was sequential part of these empires: 330-1453 AD, Byzantine (Eastern Roman)

Empire; 27 BC-330 AD, Roman Empire; 330-27 BC, Macedonian Empire; 550-330 BC, Achaemenid (First)

Persian Empire; and only then do we get back to the aforementioned "Phrygians, the Hurrians, the Hittites, the Hatti, and

the Armenians."

I suppose one should do as Bob suggests and work out when the common ancestor (or genetic mutation) occurred, and then tie

it (gently) to a particular "ethnic" group, but for now I think it will be more fun to conjecture that Richard is, say, part

Hittite or Druze... or even Ottoman (and he can conjecture about me... but I think I want my

"ancestor" to be a wanderer on the Silk Road... who eventually ended up on the Amber Road quite near their

crossing!).

HUNGARICANA

1767 Urbárium Database Follow-up #2: The 1767 Urbárium tutorial continues to draw comments... and I'm pleased

to receive and share them. HUNGARICANA

1767 Urbárium Database Follow-up #2: The 1767 Urbárium tutorial continues to draw comments... and I'm pleased

to receive and share them.

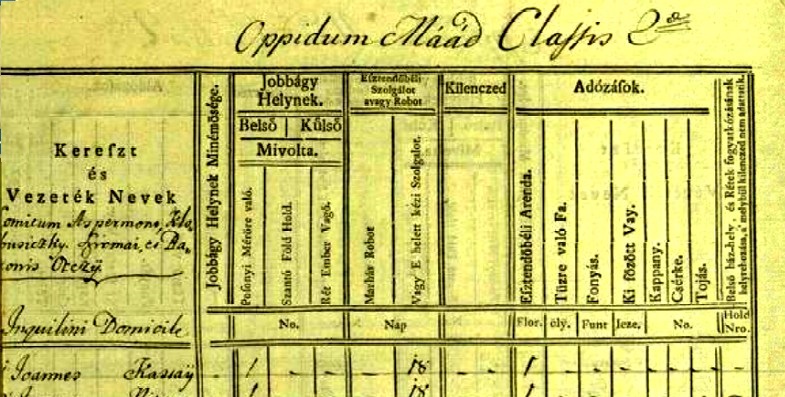

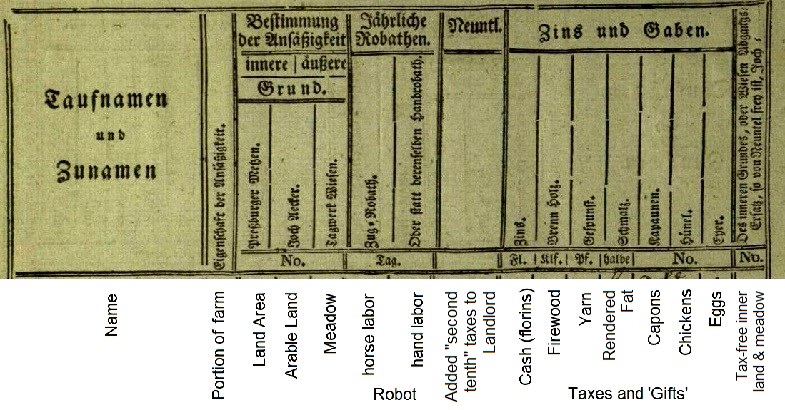

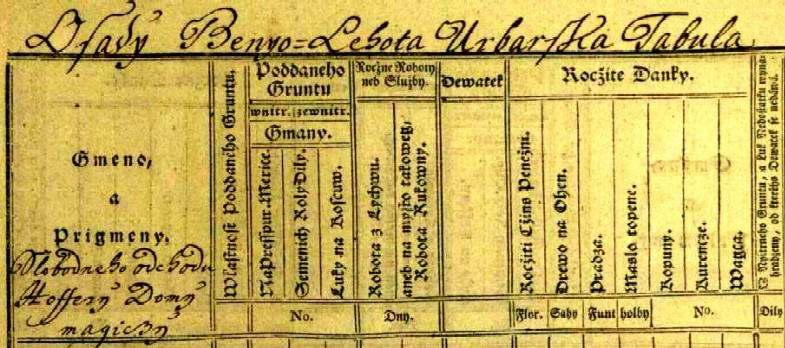

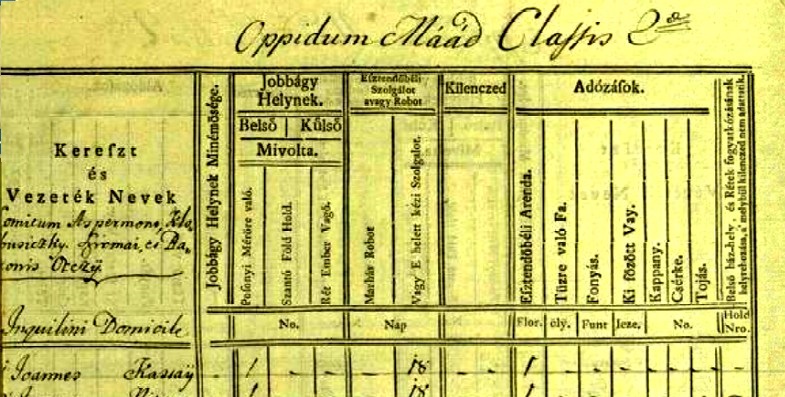

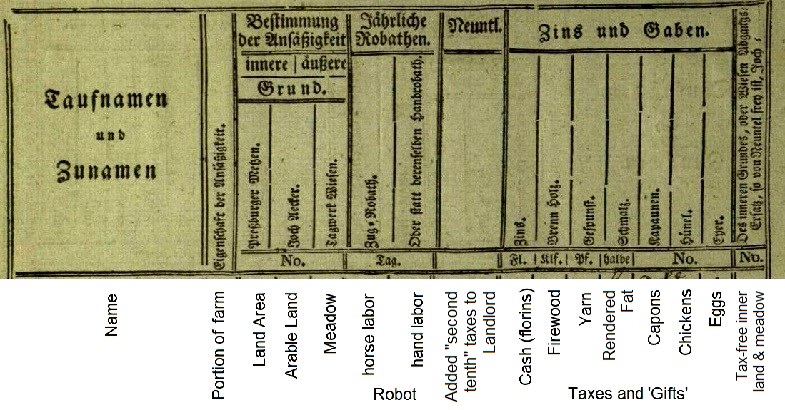

Dr. Esther Tóth, an award-winning physics teacher at the George Boronkay Grammar School and College in

Vac, Hungary, shared a copy of the Hungarian-language version of the Urbárial table headings. I had noted previously that

there were German, Latin and Hungarian variations; further research reveals there were also Slovak and Croatian versions,

but that same research failed to find an example of a form printed with Latin headings (I did find numerous handwritten

Latin headings, but those forms did not match up exactly with the pre-printed forms). I'll insert examples of the Slovak and

Croatian headers at the end of this note, but here are examples of the Hungarian form and of an annotated German form, as I

have quite a bit to say about them:

These Hungarian headings translate, in spirit, to the same English meanings as the German version I had shown previously

(but see my comments below):

First, I need to point out that I over-simplified one translation in the German version (and it is now fixed, both here and

where previously published): per Meir Deutsch, "Schmalz is fat, all kinds, not just butter. I think the

best one is from Geese." As you may recall, I had labeled the column "butter."

Now, if you look at the Hungarian version of the form, that column has text "Ki főzött Vay" ...which

GoogleTranslate claims is "Who is Vay cooked" ...which makes no sense, of course. However, Esther Tóth tells me

that "It is very interesting for me, that the Urbariums in Hungarian uses an old Hungarian. :) (I need time to understand

it.)"

With that thought in mind, I played around and discovered that the modern Hungarian "kisütött zsir" = "rendered

fats" might be a reasonable "modernization" of the Urbár's old Hungarian and a close match to the German wording.

My prior experience with translating the Hungarian headings had shown me that spelling changes or combination of

once-separate words is not uncommon... you must assume you have to play with the old words and phrases to make reasonable

sense of them (and it is much easier to do so if you have reason to believe you already know the translation). In fact, "kisütött

vaj" = "clarified butter" would also be a reasonable updating of the Urbár phrasing. Even

GoogleTranslate comes closer if you change Vay in the original text to Vaj: "Out-cooked butter" is

the new translation, and "out-cooked" is a reasonable synonym for "clarified" or "rendered."

However, Esther tells me that there actually was something called "cooked butter" in Hungary that was similar to the ghi

of India or the brown butter of France. She explains that, without cooking, unrefrigerated butter became rancid and

smelled (and there was no refrigeration in 1767!). Cooking butter at about 180 degrees Celsius (350°

F) allows it to be preserved. She says it has a beautiful smell as well, one similar to the smell of peanuts and is a

transparent yellow color. And it still exists under name "főzött vaj." So it may be that the Hungarian form actually called

for this specific butter.

She also comments that other fats may not have been as valuable in 1767 Eastern Hungary, especially pork-based fat, since

pigs, unlike other livestock, were plentiful since they were not confiscated by the Muslims during the Turkish era.

However, Western Hungary was not under Muslim rule so pork may not have been so common and its fat of higher value. These

type of arguments may explain the difference in wording for this "fat" column.

However, I'll also note here that the Slovak-language form headers are translated at this webpage:

http://www.pitt.edu/~votruba/qsonhist/urbariummariatheresa.html and that source also translates the "fats" column as

"clarified butter." (The other header column translations match well with what I provide for the German version.)

I also decided to add translations for the Neuntl column and for the last, far-right column (see below for a

discussion of the Neuntl column). The last column in the German form is one which formally indicates that homestead

land within the village proper, as well as certain fallow meadows, are free from tax. The column, if filled-in, indicates

the acreage involved. Given this was not terribly important information, some versions of the German form did not include

this column.

Interestingly, the Hungarian text for this column differs notably from the German text. According to Esther Tióth, it

translates to: "Ruined homestead land within the village, as well as fallow meadows, are free from tax if they just

recover them."

As she explains, the population density was quite low in Eastern Hungary in the 1700s (after the Ottoman were driven out)

and there were relatively large villages with few or no inhabitants. This is why German families were invited by the

Hapsburgs to resettle the land from 1711 until 1785. These families did not pay tax in the first five years at all, and they

did not pay tax even later in the case when they recultivated land, especially for grapes.

Esther and I also tossed around the meaning of the "Neuntl" column, which is written "Kilenczed"

on the Hungarian form.

Esther told me that the "Kilenczed" (the second tenth) was given to the land owner, whereas the first tenth was given

to the church (from as far back as the first Hungarian King, Stephen). However, the 1767 Urbárium was based on a new

law by Maria Theresia and spoke only about the taxes to the land owners, and nothing about the tax to the church, unless the

church was the land owner.

In reply, I told her that her comments on the “Kilenczed” column interested me because, since the rest of the

document is about labor and payments to the land owner, it seemed unreasonable that the Kilenczed should go to them

too.

This prompted her to consult with a fellow history teacher at her school, who confirmed that the data of the Urbariums

were only about the taxes to the land owners. The Kilenczed was paid only to the land owner and by the

"not-so-poor" peasants, those who had more income. He also noted that, since 1767, the churches, completely separate from

the state, collected a tax called the "Tized." At some point, that tax was renamed the "Egyházi adó" = "church

tax."

So that seems to resolve the meaning of the Neuntl / Kilenczed column. You should interpret any text and

numbers in that column as payments owed to (or deferred from) the land owner.

I'll also note that the website for the Slovak version (see link above) fully agrees with this interpretation... church

taxes were not part of this Urbárium.

Lastly, Esther noted that "In natura" translated to Hungarian as "természetbeni juttatás" = "payments

in kind". That is, you paid in eggs, milk, meat, etc. and not money.

She also noted (along with a smiley face) that, now-a-days, "if a boy helps a girl, the girl says "May I pay

In natura?" And gives a kiss."

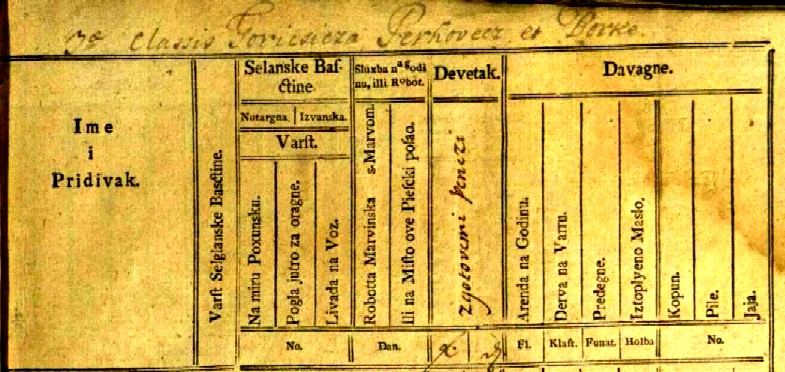

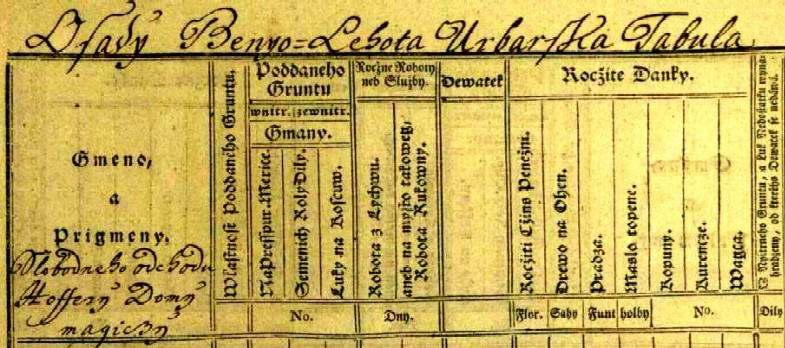

We conclude this note with the promised Slovak and Croatian header examples, starting with the Slovak

version:

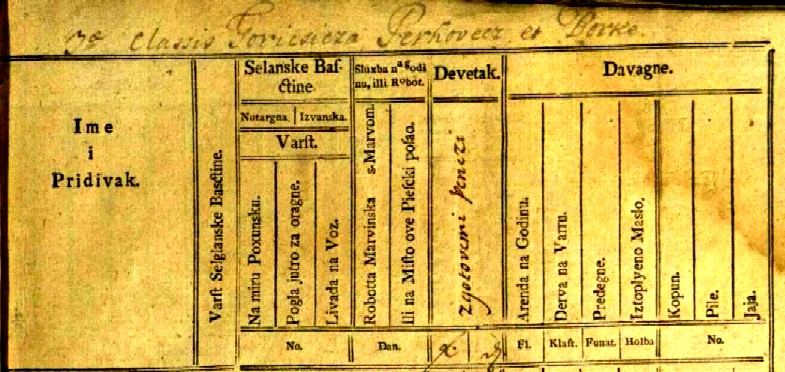

And here is the Croatian version (note the absence of the final column):

I have not attempted a translation of the Croatian form (but it seems to follow the column structure of the previous forms

so the headings likely have the same meanings).

Greenback Dollars: Last month I ended article "History and 'History' Books" with a bit of personal

history about my great-great-grandfather, Johann Steichen, and then some questions about "greenback" money. I had provide a

sentence quoted in book "History of Stearns County Minnesota" (by William Bell Mitchell, 1915) that read as follows:

"June 8, 1865 -- A German named John Steichner, just arrived from the old country, bought this week from Nicholas Rausch,

living near Rockville, twelve miles from St. Cloud, his farm of 160 acres, paying for it $1,200 in gold and $1,200 in

greenbacks."

After noting that this really was about my ancestor (despite a few errors), I asked a couple of "bonus questions," which

I'll repeat here:

Bonus Questions: What was a "greenback"? and how much was "$1,200 in greenbacks" worth in June

1865? and why do they speak of paying both "in gold" and "in greenbacks"?

Meir Deutsch was the only brave soul to offer answers to these questions... and his answers were only partially

correct, as he based his answers on the wrong era. So, herewith I try to provide the full story:

Answers: Before I researched these questions some 15 years ago, about the only thing I knew about a "greenback

dollar" was that they were mentioned in the early 1960's Kingston Trio hit song, "Greenback Dollar" (written

by Hoyt Axton in 1961). Maybe you remember the chorus:

And I don't give a damn about a greenback, a dollar

Spend it fast as I can

For a wailin' song and a good guitar

The only things that I understand, poor boy

The only things that I understand

Unfortunately, that song came out about 100 years after the advent of "greenbacks" and the meaning (simply as an

alternate name for a dollar bill) had changed substantially by then. The sentence about my great-great-grandfather was dated

June of 1865, just a few months after fighting in the US Civil War had ended... which is relevant, because "greenbacks" have

roots in the Civil War.

Prior to the Civil War, the US Government issued coins ("specie"—containing gold, or sometimes silver) as the only

legal tender. There was paper money but it was issued by private or state banks with the promise that the bank would redeem

the notes for specie on demand. However, if the bank failed, the paper money was worthless.

Back during the US Revolution, the Continental Congress had issued paper "Continental Dollars" but, since they were

backed only with a promise to redeem them for specie at some time in the future, they soon became worthless. This

soured people on trusting "money" that did not have some inherent value (such as the precious metal content of coins).

Thus, when it became apparent that the costs of the Civil War would run far beyond the government's ability to pay via its

limited income from tariffs and excises, the Lincoln Administration first sought loans from major banks, who demanded very

high interest rates. These rates were considered just too high so, in July 1861, Congress authorized $50,000,000 in what was

called Demand Notes. They bore no interest, but could be redeemed for specie "on demand." Although they were

not "legal tender," they could be used to pay customs duties. They also differed from private and state notes in that they

were printed on both sides—and green ink was used for the back side.

In December 1861, the government reneged on its promise to redeem Demand Notes for specie and began to remove

them from circulation; by mid-1863, over 95% were gone.

In

February 1862, the government first issued what they called "United States Notes," making them legal tender

for all transactions but not backing them by specie; they were backed only by the “good faith” of the US

government. These also were printed with green ink on the back and quickly became known as "greenbacks" in everyday

parlance. In

February 1862, the government first issued what they called "United States Notes," making them legal tender

for all transactions but not backing them by specie; they were backed only by the “good faith” of the US

government. These also were printed with green ink on the back and quickly became known as "greenbacks" in everyday

parlance.

The government used greenbacks to pay their soldiers and to buy goods and labor. Very quickly, however, the value of

greenbacks fell below "par" and that value varied greatly based on how poorly the war was going. At their worst, in

July of 1864, it took 258 greenbacks to buy $100 in specie.

When the war ended in April of 1865, their value rose to trade at 150 for $100 in specie. Thus “$1200 in

greenbacks” was worth $800 in specie, meaning my great-great-grandfather really paid a total of $2000 “in gold”

for the farm he bought for $1200 "in gold" (coins) and $1200 "in greenbacks" (paper).

And now you know!

A PS: The Confederate government also issued paper money during the Civil War. The Confederate dollar, often

called a "greyback," was first issued in April 1861 and also was not backed by hard assets; rather, it was backed by

a promise to pay face value plus interest to the bearer after the Southern victory and independence. Like greenbacks,

their value varied depending on the South's success during the war. Late in the war, it took nearly 1700 greybacks to

buy a single gold dollar coin; and all value was lost upon surrender.

A second PS: A question I did not ask, but that troubles me, is: Why would my ancestors emigrate to the

United States while the Civil War was raging? Were conditions in Europe (Luxembourg in particular) so bad that moving to

a country at war was better? Minnesota was far from the battle fronts, so that was a mitigating factor, but the North could

have lost the war or the sons could have been forced into military service, and avoidance of military service likely was one

reason they left Europe (I'm told that only citizens could be drafted into the US Army at the time they emigrated ...but

that could easily have changed with the misfortunes of war). It may also be that my ancestors delayed emigration until the

war ended, as it is possible that news of the April 9th end of the war could have reached Luxembourg prior to a departure

that allowed them to be in Minnesota in very early June (fast ships could make the crossing in 8-9 days in 1865). I doubt

I’ll ever know the answer to this question, but I remain curious.

Jewish Burgenland Web Resources: Margaret Kaiser recently had an email exchange with Carole Garbuny Vogel

of Branchville, NJ, who is the lead author of a article titled: "Constructing a Town-Wide Genealogy: Jewish Mattersdorf,

Hungary 1698-1939," which was first published in Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy, Vol.

XXIII. No. 1, Spring 2007. An online version of the article can be found at

http://www.recognitionscience.com/cgv/research%20mattersdorf.html.

Margaret shared her message exchange to make me aware of the article, however, I was aware of it and had previously used

some of the surname connection data found in it in a reply to a BB member. Since I agree with Margaret that it is a quite

useful article, we herewith share it with you, the BB readers.

In her message to Margaret, Carol characterized the publication as a "survey article showing many of the resources

available with information on the Mattersdorf Jewish community." She also said, "feel free to share the work

and, if you would like, to post a link to it on the website; that will be great."

Then she pointed out these additional links as quite relevant to Jewish research in Burgenland:

http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/Lackenbach/, a website "dedicated

to the study and commemoration of Jewish family history in the town of Lackenbach" and created by Yohanan Loeffler.

http://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/mattersburg/, a comprehensive

website about the Jewish community in Mattersdorf that was created by Carol Vogel.

http://www.ojm.at/blog/friedhoefe/, which is the part of the blog website

of the Austrian Jewish Museum in Eisenstadt that documents Jewish cemeteries in Burgenland.

Our thanks to Carol for sharing her work and pointing out other resources.

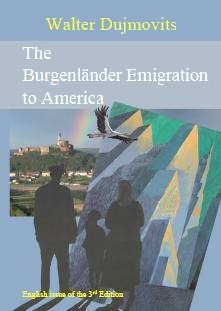

Update

for book "The Burgenländer Emigration to America": Here is this month's update on purchases of the English issue of

the 3rd edition of Dr. Walter Dujmovits' book "Die Amerika-Wanderung Der Burgenländer." Update

for book "The Burgenländer Emigration to America": Here is this month's update on purchases of the English issue of

the 3rd edition of Dr. Walter Dujmovits' book "Die Amerika-Wanderung Der Burgenländer."

Current total sales are 923 copies, as interested people purchased 14 more books this month. Surprisingly, the book's rank

improved slightly this month, to 410 from 412, likely implying that its competitors among the best-selling Lulu

books have had slower than usual sales, as this was actually a slow month for our book!

As always, the book remains available for online purchase at a list price of $7.41

(which is the production charge for the book), plus tax & shipping. See the BB homepage for a

link to the information / ordering page and for any current discounts (and there is at least one discount on price or

shipping available most of the time... if not, wait a few days and there will be one!).

Burgenland Recipes: Another recipe from cookbook "Recipes for the New Millennium" (© 2000, Morris

Press), subtitled "A Collection of Recipes from Former and Present Parishioners of Holy Ghost Church, Bethlehem, PA."

This one looks like a lot of work... but I'll bet it is worth it... plus you get two good sized rolls... should make

everyone in the family happy, twice over!

POTECA

(Nut Roll) POTECA

(Nut Roll)

(from Mary Schneider)

1 c. sour cream 5 1/2 - 6 c. sifted flour

1/4 c. milk 4 egg yolks

3/4 c. sugar 1/2 c. unsalted butter or

1 tsp. salt

margarine, softened

2 env. active dry yeast 1/4 c. honey, warmed

1 tsp. sugar Walnut Filling (recipe

follows)

1/2 c. very warm water

Combine sour cream, milk, 3/4 cup sugar and salt in a medium-size saucepan. Heat slowly, stirring constantly, just until

mixture begins to bubble and sugar dissolves; cool in large bowl.

Sprinkle yeast and the 1 teaspoon sugar into very warm water in a 1-cup measure. (Very warm water should feel comfortably

warm when dropped on wrist.) Stir to dissolve. Let stand until bubbly, about 10 minutes.

Stir yeast into cooled sour cream mixture; beat in 3 cups of the flour until very smooth. Cover bowl with clean towel; let

rise in a warm place, away from drafts, 1 hour or until doubled in volume; beat mixture down.

Beat egg yolks until well blended in a medium-size bowl; beat in very soft butter until smooth. Beat egg/butter mixture and

enough of the remaining flour into yeast mixture to make a soft dough.

Turn out onto lightly floured surface and knead 10 minutes or until dough is smooth and elastic. Place in a large buttered

bowl; turn to bring buttered-side up. Cover; let rise in a warm place, away from drafts, 1 hour or until doubled in volume.

Punch dough down; knead a few times. Let rest 5 minutes. Divide dough in half; roll one-half on a lightly floured surface to

a 26 x 10 inch rectangle. Spread half the walnut filling over dough, leaving 1/4 inch margins.

Roll up jelly roll fashion, starting with one of the short ends. Pinch to seal seam; turn ends under, pinching to enclose

filling. Place, seam-side down, on a greased cookie sheet. Repeat with the remaining dough and filling to make a second

cake. Cover; let rise in a warm place, away from drafts, 1 hour or until almost doubled in volume.

Bake in a moderate 350° oven for 35 minutes or until cakes are golden. Cool on wire racks. Brush cakes with warmed honey;

sprinkle with reserved chopped walnuts, if you wish.

Walnut Filling for Poteca:

1 lb. shelled walnuts

3/4 c. sugar

4 egg whites, at room temperature

Finely chop or grind walnuts; make sure that the nuts are very fine, so that the cake will cut neatly. Reserve 1/4 cup for

garnish, if you wish. Beat egg whites until frothy. Add sugar and nuts. Mix well.

Cartoon

of the Month: Cartoon

of the Month:

A different take on DNA research...

|

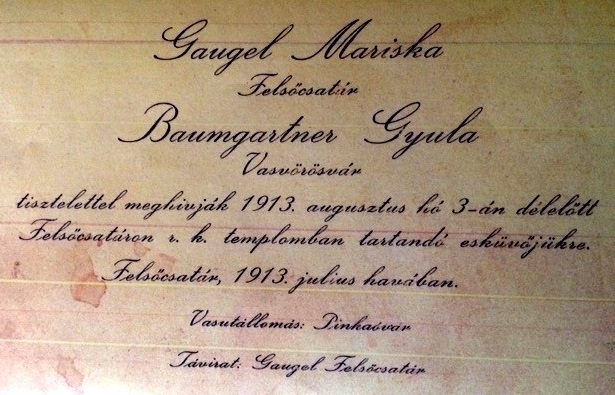

2) A HUNGARIAN WEDDING INVITATION

Recently, the BB received a New Member Information Form from Willemijn and Richard Baumgartner of Fairfax, VA. It

indicated that Julius' ancestors, Julius and Mariska (Gaugel) Baumgartner married in 1913 and emigrated the next year

to Chicago, IL, where he set up an auto repair shop and they lived out their lives. Both Julius and Mariska were noted as

being from Rotenturm, though there was a question mark placed after that village for Mariska; her surname also had

Gangl given as an alternate spelling. However, what caused me to do some research and to write back to Willemijn and

Richard was that Julius was indicated as being born in 1887 and Mariska in 1871. This struck me as too large an age gap and,

relative to what typically occurred when there was a gap in age, it was a gap in the wrong gender direction.

After completing some initial research, I wrote saying:

Is the “born 1871” an error for Mariska? I presume it is supposed to be 1891, yes?

If so, I think they arrived Jan 1, 1914 at Ellis Island on the SS Barbarossa from Bremen under transcribed surname

Baumgarten and given names Gxula and Maria. He is listed as 26 and she as 23. Gyula is the

Hungarian form of Julius and Maria/Mariska go together. They were listed as coming from village

Vorosvar (Rotenturm) and born in villages Vorosvar and Schilding (now Alsó- and

Felsö-Csatár, Hungary).

Based on the above birth villages, I found the marriage record in the Felsö-Csatár records (see attached). It gives

parental names and exact birthdates.

Although I had not mentioned it in the above email note, Julius/Gyula/Gxula was listed as a mechanic on the Ellis Island

passenger manifest, so that matched what Willemijn and Richard had put on their Member Information Form. However, as

I confirm my facts for this article, I now see that the departure village and Julius' village of birth was spelled

Vorovar (rather than the Vorosvar I put into my email note or the fully correct Vasvörösvár) and that the

final destination was listed as New York (not Chicago!) ...however, the manifest indicated that Julius had been in Chicago

in 1907 and 1913. In addition, the manifest listed mother Franciszka Baumgarten of Vorovar as nearest

relative... and that motherly first name matches what was on the marriage record.

As for that marriage record, it listed Julius under the Hungarian form Gyula and Mariska as Mária Gangel.

Mariska is a Hungarian diminutive of Mária, so that ties together, but the spelling of her last name added one more

variation to the Gaugel and Gangl of the Information Form.

Having observed many Croatian surnames, my immediate reaction was that a Gaugel spelling would be very unlikely in

West Hungary (the “u” in it almost certainly a misreading of a German Kurrent handscript “n” … in fact,

the marriage record seemed to support this in that the handscript “u” in Baumgartner had the

characteristic mark above it, ŭ, while the handscript n in Gangel was

without the characteristic mark but otherwise similar to the handscript u). Further, both Gangel and Gangl were

common surname spellings in West Hungary, arising out of a Croatian background, with the Gangl spelling the more

common, so I felt a Gaugel spelling must be a simple misread of script writing... and I told Willemijn and Richard so.

As for other data in the Felsö-Csatár marriage record, the couple was married 3 Aug 1913 and Gyula/Julius was born a

Roman Catholic on 14 Oct 1887 in Vasvörösvár with current occupation of lakatos (fitter/metal worker/mechanic) ...all

consistent with Willemijn and Richard's data. Julius' parents were shown as the deceased (néhai) Ferenc Baumgartner

and Franciska Tallián (so Franciska's name as nearest relative on the passenger manifest makes sense).

Mária/Mariska was reported as born a Catholic on 2 May 1890 in Felsöcsatár to parents Ferenc Gangel and Teréz Fiksel. Her

birth date was not inconsistent with the provided 1891 date (as the year is often reported as one year more recent than

correct when it is calculated from age in a given year). The Felsöcsatár birth location, however, denied the

Rotenturm? location given on the Information Form, so Willemijn and Richard's questioning of her birth location

was correct.

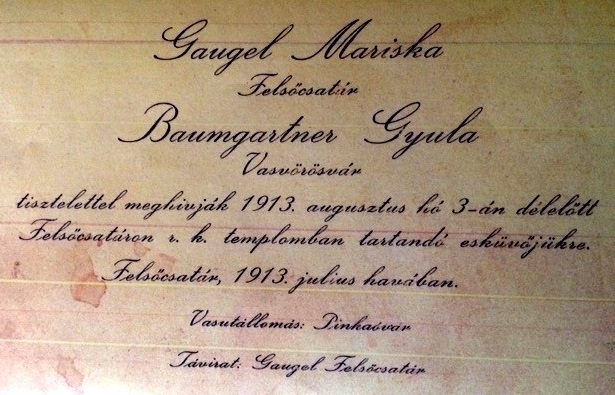

By now, I presume you are questioning why I titled this article "A Hungarian Wedding Invitation" as, so far, I had

yet to mention it. We get to it now!

In response to my email message shown above, Willemijn responded, saying (in part):

You are absolutely right about the 1891 birth year for Mariska. Thank you so much for your response and the updated

information on Richard's grandparents. We have a marriage invitation in Hungarian that we have managed to translate and

found pictures of the church.

That prompted me to write back saying (in part):

I’m quite curious about the Hungarian wedding invitation you have. Yours is the first one I have ever heard about

coming from West Hungary! Is it possible for you to send a good scan of it to me? and possibly your translation? I might

want to put a note in our newsletter about it (if that would be OK with you). If so, a copy of the picture of the church

and the participants would be nice to include also.

My reason for asking about the wedding invitation (beyond just personal curiosity) was that, too often, much of what I

write in the BB newsletter is about the harder side of the European life our emigrant ancestors left behind, forgetting that

niceties like wedding invitations existed. I hoped that reporting on this wedding invitation might help round out the

picture I try to paint for the readership.

Willemijn kindly wrote back with photos of both the invitation and the church, as well as a rough translation of the

invitation's text. Here is the invitation:

Rather than present the rough translation as provided by Willemijn, I took some time to refine it, coming up with the

following:

|

Gaugel, Mariska

Felsöcsatár

Baumgartner, Gyula

Vasvörösvár

cordially invite you on 3 August 1913 in the pre-noon

to their wedding to be held at Felsöcsatár Roman Catholic church.

Felsöcsatár, the month of July 1913

Train station: Pinkaóvár

Telegram: Gaugel Felsöcsatár |

So, there you have it... sweet and to the point, but with no exact time specified. However, Réka Kieß tells me that the

Hungarian word délelőtt literally translates as prior to noon, and that Hungarians differentiate between

morning hours, which last until about 9 am, and the rest of the morning, which is specified as pre-noon. Thus she

believes that the wedding likely took place right after completion of the 9 am morning mass and that the mass attendees

remained as the two were given in marriage.

The invitation even kindly indicated which train station to use and how to send a telegram. The train station still exists

north of Burg (Pinkaóvár) in Burgenland, though it appears to be long abandoned, with the tracks overgrown:

Interestingly, the bride’s last name on the invitation is clearly “Gaugel” rather than “Gangel” …this

surprised me! I truly thought Gangel/Gangl derived from Croatian origins, so to see it recorded definitively as Gaugel

was a shock. It may not be, in fact, a Croatian-based surname (but I still think it is a variation on Gangl, as the

Gaugel spelling is extremely rare and points only to Austria, Hungary or, when more specific, to the West Hungary

border area; further, Mariska Gaugel was known to speak Croatian, which would be unlikely if that were not her roots).

As for the Felsöcsatár church, it was (and is) Szent Miklós (St. Nicholas) by name. Below are pictures of it and its

location nestled in the center of Felsöcsatár.

For curiosity, I decided to try to find the baptism records for the wedding couple. Despite some reservations

based on spelling variations and inexactness of dates, I'm convinced these are the correct records:

Name Gyula Baumgartner

Event Type Baptism

Event Date 16 Oct 1887

Event Place Vörösvár, Vas, Hungary

Gender Male

Father's Name Ferencz Baumgartner

Mother's Name Sani Talian

Name Maria Gerugel

Event Type Baptism

Event Date 04 May 1890

Event Place Nagynarda, Vas, Hungary

Gender Female

Father's Name Ferencz Gerugel

Mother's Name Theresa Jekszl

Nagynarda was the Catholic recording parish for Felsöcsatár at that time and Vörösvár is what is in the

records for Vasvörösvár, so baptism locations are not an issue.

As for the dates, both baptism dates are two days after the birth dates reported in the marriage record.

Coincidentally, both birth dates were Fridays and both recorded baptism dates were Sundays. Nonetheless, it was more common

for baptisms to be performed on the day of the birth or the day after the birth, if the birth occurred late in an evening.

Still, these baptism and birth dates are close enough not to warrant great concern. It may be that the priests did their

"paperwork" on Sunday and inadvertently recorded that date rather than the baptism date, or were just not available for a

baptism on Saturday (but, of course, were available on Sunday). Likewise, it may be that the parents chose to wait a day,

knowing they were going to the church for the Sunday service anyway.

If you recall the marriage record that I described near the beginning of this article, it had generally clear writing so I

think I know the correct parental names. Thus, given the difficulty in transcribing old records, I could see Frani

(for Fransziska) being mis-transcribed as Sani in the transcription of the above birth record. Likewise, given the

phonetic way of recording surnames in Hungary at that time, Talian for Tallián is no great stretch and,

combined with transcription problems, Gerugel for Gaugel and Jekszl for Fiksel are in the realm

of probable matches (however, which ones are the "correct" spellings can't be determined from this limited data!).

[Ed. note, 2017: With the digitization of the Burgenland microfilms, I was able to look at the records and

confirm my suspicions about the names. Rather than Sani, Fani was recorded, and Talian for Tallián;

further, it is Gaugel and Fikszl in the other birth record.]

Based on my experience, I find all of these differences to be consistent with typical transcription errors, spelling

variations or possible phonetic variations. While I would advise obtaining the microfilms to verify what really had been

written, I remain convinced these are the correct records.

I hope you've enjoyed this little trek into the past. I find it comforting to know that a couple that was obviously

intending to leave West Hungary for America and a better life (they were ship board two months later and the husband had

been in America earlier in the year) would bother with formal wedding invitations, complete with travel and contact

instructions. I do, though, wonder if they ever went back to the Heimat...

|

3) RESEARCHING MY HAIDER ANCESTRY (by Cheryl Richardson)

I

became interested in researching my Haider ancestors following the death of my mother, Marcelle Haider, in 2012. As

my sister and I were sorting through old photographs and correspondence, we found a letter written in 1957 by a Marie

(Haider) Winbauer Hanson to her niece, Theresa Haider, in which she enclosed an old postcard from Illmitz along with some

photographs. In this letter she gave her age as 82 (implying born 1875-6) and mentioned a brother Andrew and his wife

Barbara. On the envelope, my mother had written “Aunt Mary Haider Winbauer.” This letter would later be a clue to

finding the correct George Haider, my great-great-grandfather. I

became interested in researching my Haider ancestors following the death of my mother, Marcelle Haider, in 2012. As

my sister and I were sorting through old photographs and correspondence, we found a letter written in 1957 by a Marie

(Haider) Winbauer Hanson to her niece, Theresa Haider, in which she enclosed an old postcard from Illmitz along with some

photographs. In this letter she gave her age as 82 (implying born 1875-6) and mentioned a brother Andrew and his wife

Barbara. On the envelope, my mother had written “Aunt Mary Haider Winbauer.” This letter would later be a clue to

finding the correct George Haider, my great-great-grandfather.

My mother’s father was Frank W Haider, who was born in North Dakota in 1894 to Michael Haider and Elizabeth

Millner/Müller. Both Michael and Elizabeth were born in Illmitz and had immigrated to the USA in 1883. Using

FamilySearch and Ancestry, I was able to find Elizabeth’s baptism record easily, which revealed her parents’

names as Josephus Müller and Theresia Kroiss.

Michael and Elizabeth (Müller) Haider family, circa 1909

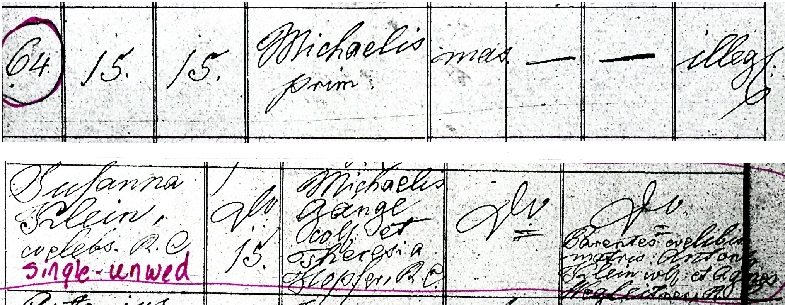

However, on-line searching for my great-grandfather Michael Haider’s baptism record from Illmitz came up

empty. I later discovered this was because I was searching using his full name rather than just his first name, date of

birth and location (I know this sounds odd... but read on, it will make sense!). A death certificate listed his father as

George Haider, with the mother’s maiden name listed as unknown.

In order to find Michael's baptism record, I made my first trip to the local LDS Family History Center in January

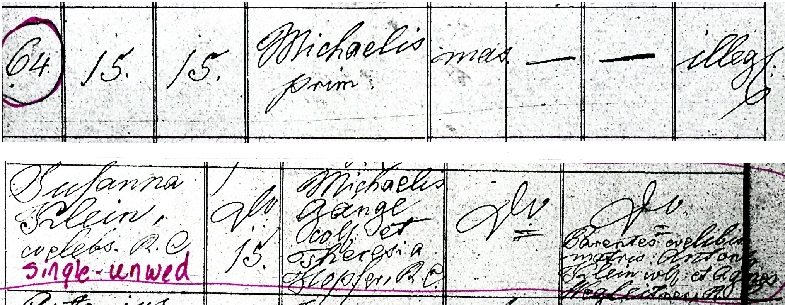

2015, where they had a copy of FHL film #700866. I was successful in finding the baptism record for Michael (see below) but

was in for a shock. Michael was born 15 Oct 1859 to a Susanna Klein. The record indicated it was an

illegitimate birth. No wonder I could not find this record during my on-line search—I had searched using Michael

Haider. Now I had the house number where he was born (#15 Alsó-Illmitz), his mother’s name and her parents’ names of

Antonius Klein and Agnes Wegleitner, but no father was named. No one in my family had any idea his birth was illegitimate or

had ever heard of the Klein or Wegleitner surnames. Were we even Haiders?

Baptism record for Michael Klein, 15 Oct 1859, Alsó-Illmitz (placed on two lines for readability)

In April 2015, I headed back to the LDS Family History Center and located the marriage record for Michael

Klein/Haider and Elizabeth Müller, who were married in 1882. Again, no father's name was listed for Michael and he used the

Klein name on this record. It appears that Michael and Elizabeth got married right before departing for the USA

around 1883.

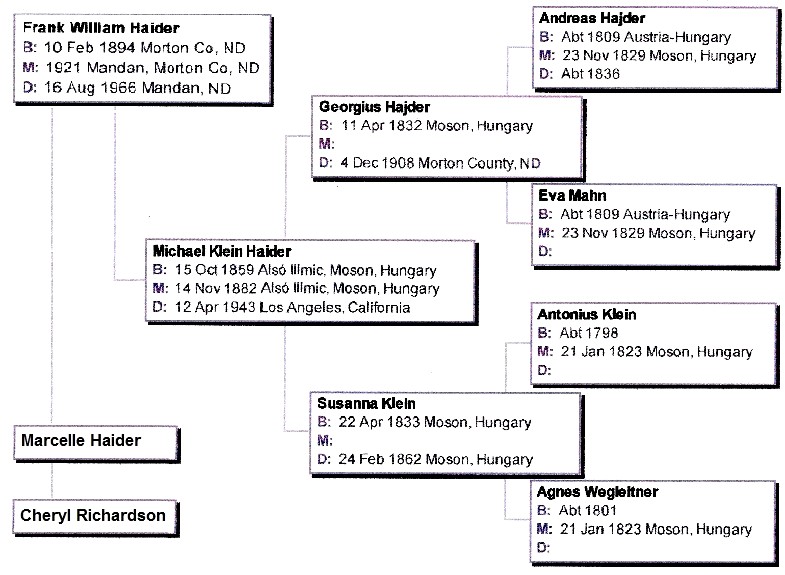

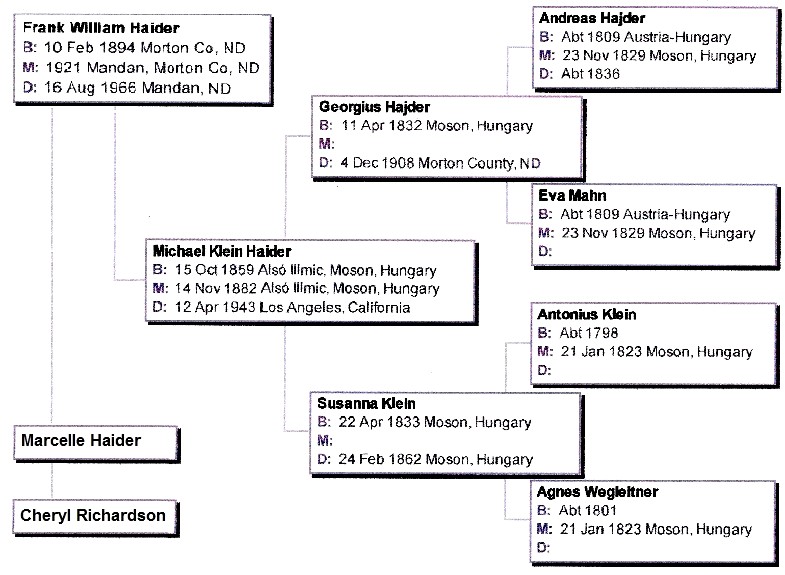

Next I wanted to try and find out which George Haider was my great-great-grandfather. There were 3

possibilities that I found. Using Ancestry, FamilySearch, and the BB's BH&R and Houselists, I

narrowed my George Haider down to one who was born in 1832 in Illmitz and had later married a Maria Göltl. They immigrated

to the USA in 1887 with a group of 10 other people from Illmitz.

I returned to the LDS Family History Center and located baptism records for the children of George Haider and

Maria Göltl. I found that their first four children had the exact same godparents, Michael Gangl and Theresia Hopfer,

as did my Michael Klein / Haider. Their children were all born in house #25 Alsó-Illmitz. They had a son named András

(Andrew) and a daughter named Maria, b. 1876. I then remembered the letter from Maria Haider Winbauer that I

had found in my mother’s possession: Aunt Maria (Haider) Winbauer was 82 in 1957, implying born 1875-6, and had a brother

Andrew. This cinched it. I was sure I had found the right George Haider.

My next stop would be to Illmitz in June 2015.

DNA Family Finder

In preparation for a visit to Illmitz in June 2015, I decided to have FamilyTreeDNA complete a Family Finder

test to find out where my ancestors were from and to see if I could find any matches with potential living relatives. The

test did reveal my origins are 97% European and 3% Central/Southern Asian (Turks). I also joined the Burgenland DNA

Project at that time.

In March 2015, I was contacted by Ewald Hasun, who lives in Austria. We were a DNA match and were estimated to be 2nd to 4th

cousins. At that time, the only surname we thought we had in common was Haider. His ancestors had also come from

Illmitz. Our shared autosomal DNA in centiMorgans is 58.97.

When Ewald found out that my husband Mark and I would be visiting Illmitz in June, he and his girlfriend Christa made

arrangements to meet and spend 2 days with us there.

Collaboration

We both did some research and I found out my Haider, Klein and Müller ancestors lived in house #’s 15,

25 and 53 in Alsó-Illmitz. I found that Ewald’s great-great-grandparents, Florianus Hajder and Anna Mann/Mahn, lived in

Alsó-Illmitz house #173, and Ferenc Frank and Ann Hajder lived in Felsö-Illmitz house #43. The house #’s just started to be

listed on the baptism registers in 1854.

Ewald and Christa made a trip to Illmitz prior to June and found out that the cemetery was built in 1778 ...but there were

no old headstones. The oldest dates they could find were around 1890. Ewald also tried to find the current locations of

house #’s 15, 43, 53 and 173 by checking with the Illmitz City Hall. Ewald sent me a map of Illmitz with the locations of

the houses marked.

I wrote to the Illmitz parish priest in May 2015 to find out if we could visit his parish and look for marriage and baptism

records from 1858 to 1864. The priest wrote back and told me that they only had marriage records beginning in January 1876

and that the older records were at the diocese archives in Eisenstadt.

Ewald went to Eisenstadt just prior to meeting us in Illmitz and found the marriage register for my

great-great-great-grandparents, Andreas Hajder and Eva Mahn, which provided the names of their parents, Georgius

Hajder and Agnes Frank. He also found the baptism record for my great-great-grandfather, Georgius Hajder. He provided me

with copies when we met in Illmitz.

Our Time in Illmitz

On

our first day in Illmitz, we met Ewald and Christa for lunch and wine and got to know each other better, then they took us

on a walking tour of Illmitz. We visited the cemetery and looked at the headstones with all our family surnames (the grave

sites are very well cared for by family members and are decorated with live flowers). On

our first day in Illmitz, we met Ewald and Christa for lunch and wine and got to know each other better, then they took us

on a walking tour of Illmitz. We visited the cemetery and looked at the headstones with all our family surnames (the grave

sites are very well cared for by family members and are decorated with live flowers).

Next we walked to the addresses of where Ewald had been told the houses of our ancestors had been located. However, we found

that there is confusion about where these houses were located due to Illmitz being split, historically, into two parts—Unterillmitz

(Alsó-Illmitz) and Oberillmitz (Felsö-Illmitz). According to the

gemeinde-illmitz.at website, Illmitz was divided between Unterillmitz and Oberillmitz until 1905. The

marriage and birth registers for our ancestors showed that house #’s 15 (Haider/Klein), 53 (Kroiss/Müller) and #173 for

Ewald’s (Florian Haider/Anna Mahn) were in Alsó-Illmitz and the house of Ewald’s ancestor (Franz Frank) as house #43 was in

Felsö-Illmicz.

Ewald had made contact with the current resident of house #15 Alsó-Illmitz and she said that her ancestors were not

my Haider/Klein family. Ewald is working on trying to verify the true locations of our ancestors’ homes. [Ed note: The

1856 Illmitz BB Houselist indicates house #15 in Unter/Alsó-Illmitz was owned by Anton Klein and wife Agnes Wegleitner,

putative parents to Susanna Klein and grandparents to Michael Klein / Haider. Coincidentally, house #15 in Ober-Illmitz was

owned at that time by a Martin Wegleitner and wife Rosalia Koller.]

Ewald and Christa took us to Florianigasse 8, where some original houses from the 1800s, made in the Hungarian style

with thatched roofs, still remain and are in the process of being restored. While there we met Robert, a local resident and

nature photographer, who offered to show us his home that was built in 1891. Robert and his wife, Sylvia, gave us a tour of

their home and shared some wine and stories with us in their courtyard. It was a memorable and unexpected experience.

Ewald

made an appointment that afternoon with Mag. Anna Haider to look at the marriage, death and baptism records

maintained at Illmitz' St. Bartholomäus Roman Catholic parish. Contrary to what I had been advised by the parish

priest, we discovered that the parish did have records going back prior to 1876. Ewald and I were both successful in

finding records for some of our ancestors. Ewald

made an appointment that afternoon with Mag. Anna Haider to look at the marriage, death and baptism records

maintained at Illmitz' St. Bartholomäus Roman Catholic parish. Contrary to what I had been advised by the parish

priest, we discovered that the parish did have records going back prior to 1876. Ewald and I were both successful in

finding records for some of our ancestors.

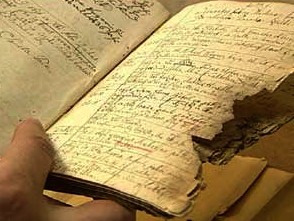

Ewald had noticed that the baptism and marriage registers he found in Eisenstadt looked different than the copies I had

obtained from the FHL Films 700866 and 700867 for Illmitz, so we were wondering whether there were two sets of records

maintained for baptisms, marriages and deaths for Illmitz.

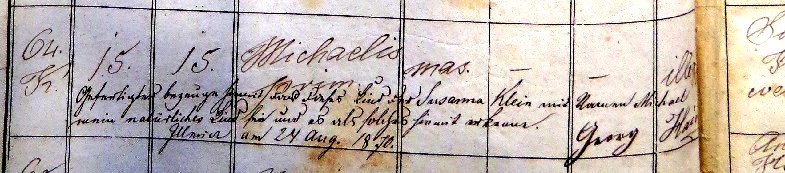

Because of the differences, I decided to look at the baptism record of my great-grandfather, Michael Klein / Haider,

and to compare it to the copy I had from the FHL film. Lo and behold, there was additional verbiage, written after

the fact, on his baptism record in the Illmitz parish register.

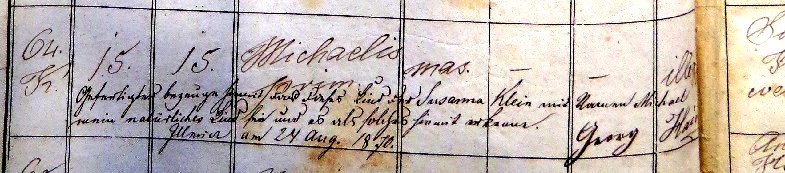

Tom Steichen provided the following information after reviewing the document: It is written in the old German “Kurrent”

handscript and reads “Gefertigter bezeuge hiemit dass dieses Kind der Susanna Klein mit Namen Michael Mein natürliches

Kind sei und es als solches hiemit erkenne.” This translates to “The undersigned testifies herewith that this child

of Susanna Klein was my natural child by the name of Michael and hereby acknowledges it as such.” The Hungarian village

name (Illmicz) and the date (am 24 Aug. 1870 = on August 24, 1870) were also provided and it was signed by Georg

Haider:

Annotated baptism record for Michael Klein, 15 Oct 1859, Alsó-Illmitz

I was overjoyed! This provided the proof that I had been seeking that my great-grandfather, Michael Klein, was, in fact, the

son of George Haider. This discovery alone made the visit to the Illmitz parish worthwhile.

Ewald and Christa made our time in Illmitz very meaningful. The next day, they took us on a tour of the area, including the

Neusiedler See-Seewinkel National Park Information Center, Strandbad, a beachfront park with ferry service and restaurants, and to various bird-watching outpost points on the

lake. Mark and I got to experience bird watching in the National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site, with Ewald and

Christa, who are very knowledgeable about the wide variety of birds in the region. We also enjoyed some local cuisine and

wine at some of their favorite restaurants.

Strandbad, a beachfront park with ferry service and restaurants, and to various bird-watching outpost points on the

lake. Mark and I got to experience bird watching in the National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site, with Ewald and

Christa, who are very knowledgeable about the wide variety of birds in the region. We also enjoyed some local cuisine and

wine at some of their favorite restaurants.

The people of Illmitz were very friendly and welcoming. We were even treated to a tour of the winery at Arkadenweingut

Gästehaus Familie Heiss by the elder Hans Heiss, who is in his early 80s and still works every day in the winery. He

generously opened four bottles of different wines for us to taste. One bottle was from 1992, and it was a special honor that

he shared it with us.

We were fortunate that, during our stay in Illmitz, the town was having their Summer Village Festival in the

evenings, with wine, food and music, so we could enjoy the festivities with Ewald, Christa and the local people.

As a parting gift, Ewald and Christa presented us with a picture book of the National Park Neusiedler See-Seewinkel

to remind us of Illmitz, the beautiful surrounding nature and of them. Mark and I will never forget our time in Illmitz with

Ewald & Christa and of the local people we met.

Ewald and I still have not uncovered which direct ancestor we share. We are still working on making that discovery. We now

know that we have the surnames of Hajder/Haider, Frank, Mahn/Mann, Tsida/Tschida and Gartner in common.

Since our meeting in Illmitz, Ewald and Christa returned to Illmitz and Eisenstadt and found some records dating back to

1798. This is of great benefit to me because the Illmitz records on the FHL films only go back to around 1823. I have

continued to do research by using Ancestry, FamilySearch and by visiting the local LDS Family History

Center to review the microfilmed Illmitz records. Ewald has compiled all the information on his computer, which has

helped provide us with an overview of where our connections may be. By collaborating together we have made great progress on

filling in the blanks on our family trees.

Partial Haider family tree, connecting the main individuals in this ancestral story

For those of you who are planning to take a trip to Burgenland, it is an easy one-hour drive from Vienna. Besides going to

Burgenland to discover your ancestral roots, I can also recommend the region for the warmth of the people, the nature and

beauty, the fine wines and cuisine, and the outdoor activities of cycling, bird watching, horseback riding and sailing.

|

4) TUTORIAL III: 1720 AND 1715 URBÁRS

Warning: Since this BB Newsletter tutorial article was written, the site holding the

Urbárs has been reimplemented and the exact steps given in the article no longer apply. However, the current (2021) web

implementation is quite similar so the tutorial can still be useful... but do expect screen images to look somewhat

different and approaches to have minor differences!

The new web locations for the Urbárs are:

■ 1715 Urbariam:

https://adatbazisokonline.hu/adatbazis/az-1715_-evi-orszagos-osszeiras/hierarchia

■ 1720 Urbariam:

https://adatbazisokonline.hu/adatbazis/az-1720_-evi-orszagos-osszeiras/hierarchia

It appears that the Cross-reference of Urbárial Village Names that appears in the article that immediately follows

this one remains correct (however, this statement is made based only on a quick and superficial review).

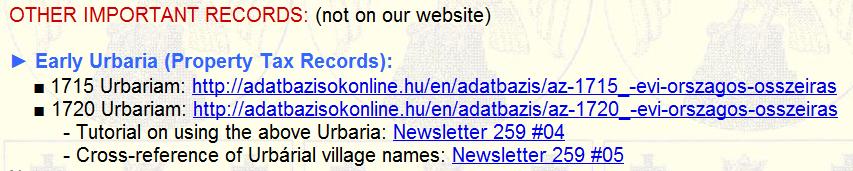

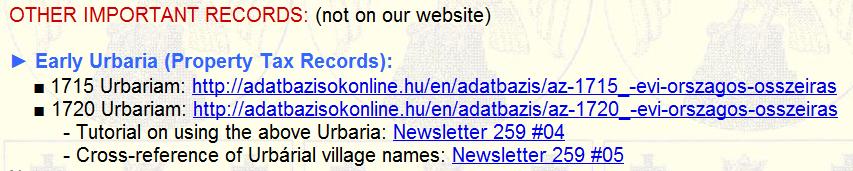

Although I have been doing tutorials for resources on the HUNGARICANA website, this time I've chosen to bring attention to

an outside resource that we directly link to via the BB website, that being the 1720 and 1715 Urbáriums on the

Hungarian National Archives' AdatbázisokOnline (Databases Online) site. Actually, these Urbárs are

available via the Hungaricana site too ...but it is far easier to use the BB's direct links.

First, however, I must give you the usual warning: you should not expect anything real useful to be presented in English!

This is a Hungarian site and almost all descriptive or instructional text is in Hungarian. But do not be discouraged... it

is actually quite easy to use the site (other than one design flaw... but that is not a language problem).

Like the 1767 Urbárium that I described in BB Newsletter #257, the 1720 and 1715 Urbárs were listings of

people who owed taxes and labor to the local nobility. I will not go into much detail about the content of those listings,

rather, I will concentrate on helping you get to the ones you want. If you looked at the 1767 Urbár, it makes good

sense that you might wish to extend your family research back to this somewhat earlier time.

For the tutorial, I will use the 1720 Urbár... however, the 1715 Urbár is set up similarly to the 1720

one so it should be easy to transfer these instructions to it (there is a minor difference that I'll explain at the

appropriate point). I make this choice because Vas county was not included in the 1715 Urbár, thus making

1720 useful to more BB researchers. You can find the links to these Urbárs near the bottom of the BB home page...

the section you would look for looks like this:

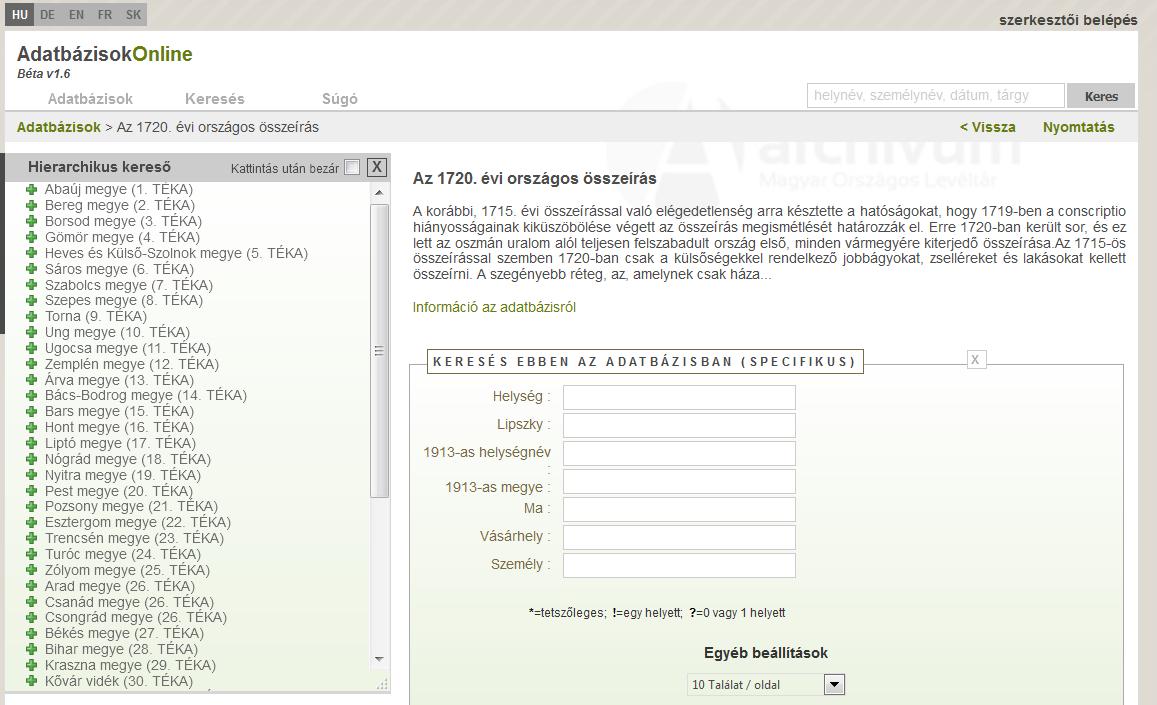

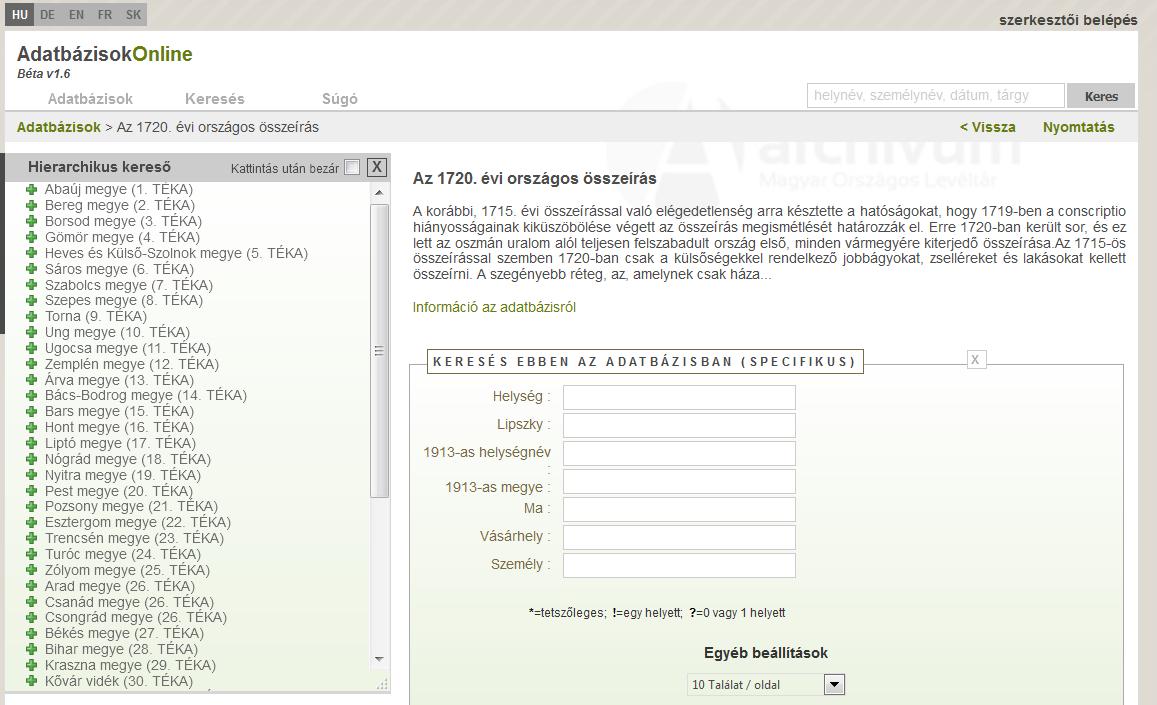

Clicking on the link for the 1720 Urbárium will take you to its main page. I'll

repeat the link here so you can more easily access it:

http://adatbazisokonline.hu/en/adatbazis/az-1720_-evi-orszagos-osszeiras.

The main page should look something like the image below:

The only thing on this page that you'll be interested in is the Hierarchikus kereso (hierarchical search) section on

the left that has the scrolling list of megye (county) names with the green plus signs:

. .

For my example, I'll again use Ginger McGurk's village of interest Apetlon, where she has Klein

ancestors. Apetlon's Hungarian name is Bánfalu, and it was in Moson megye. As I've mentioned before,

all of Burgenland came from three pre-1921 Hungarian counties, Moson, Sopron and Vas. In the scrolling list, they appear

toward the bottom, so the first thing to do is grab the grey scroll bar and pull it down to reveal the lower part of the

list (you can also position your mouse cursor in the list and use your mouse wheel to move the list up or down.

This gets us to part of the design flaw I mentioned above... the scrolling list is actually an independent

"window" that is tied to a particular spot on the underlying page... if the list is too long, it can stretch off the

page and you won't be able to see the last lines. This occurs if you have "zoomed" your browser page to make everything

bigger (which I tend to do). If you do too, you will need to reduce your zoom to make the whole scrolling list visible.

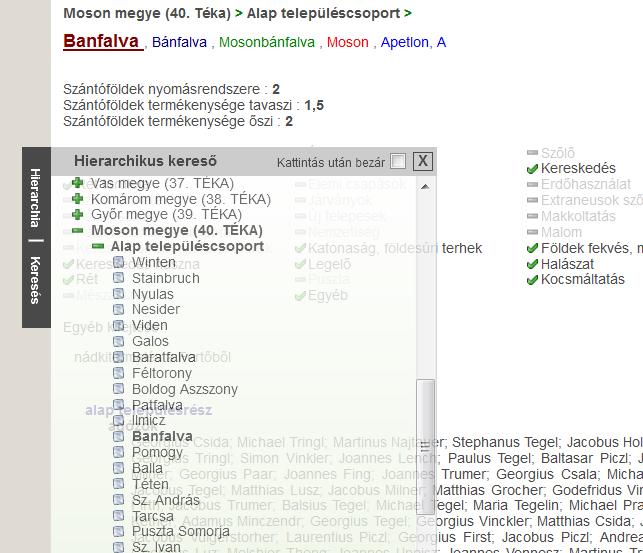

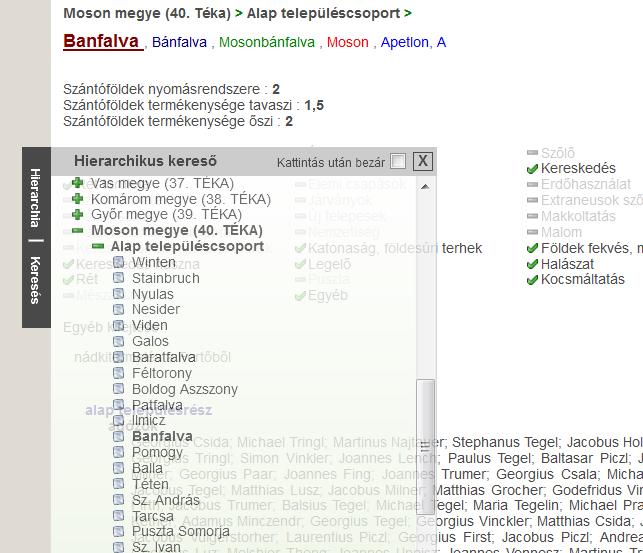

You

should find "Moson megye (40. TÉKA)" near the bottom of the list (40. TÉKA just means "library 40"). Click on the green

plus. Then click on the next green plus for the sub-list (titled Alap településcsoport = basic settlement group) that

is indented. Having done so, you should have a display that looks something like the clip to the right, where the clicked

plus signs are now minus signs. You

should find "Moson megye (40. TÉKA)" near the bottom of the list (40. TÉKA just means "library 40"). Click on the green

plus. Then click on the next green plus for the sub-list (titled Alap településcsoport = basic settlement group) that

is indented. Having done so, you should have a display that looks something like the clip to the right, where the clicked

plus signs are now minus signs.

Note that the village names are not arranged alphabetically, so you will need to do some scrolling and searching to

find the village you want. Also note that the listed village names are a mix of German and Hungarian names (and sometimes

I'm not sure what), often badly misspelled but just as often having some vague phonetic resemblance to a correct Hungarian

or German village name. Moson County is actually pretty easy to decipher, as most listed names are close to a correct

Hungarian village name.

As you might expect, clicking a minus sign will close any sub-lists under them and return to the unclicked view. However,

the villages have a little "page" icon, which indicates that clicking them will take you to a data page rather than open

another sub-list.

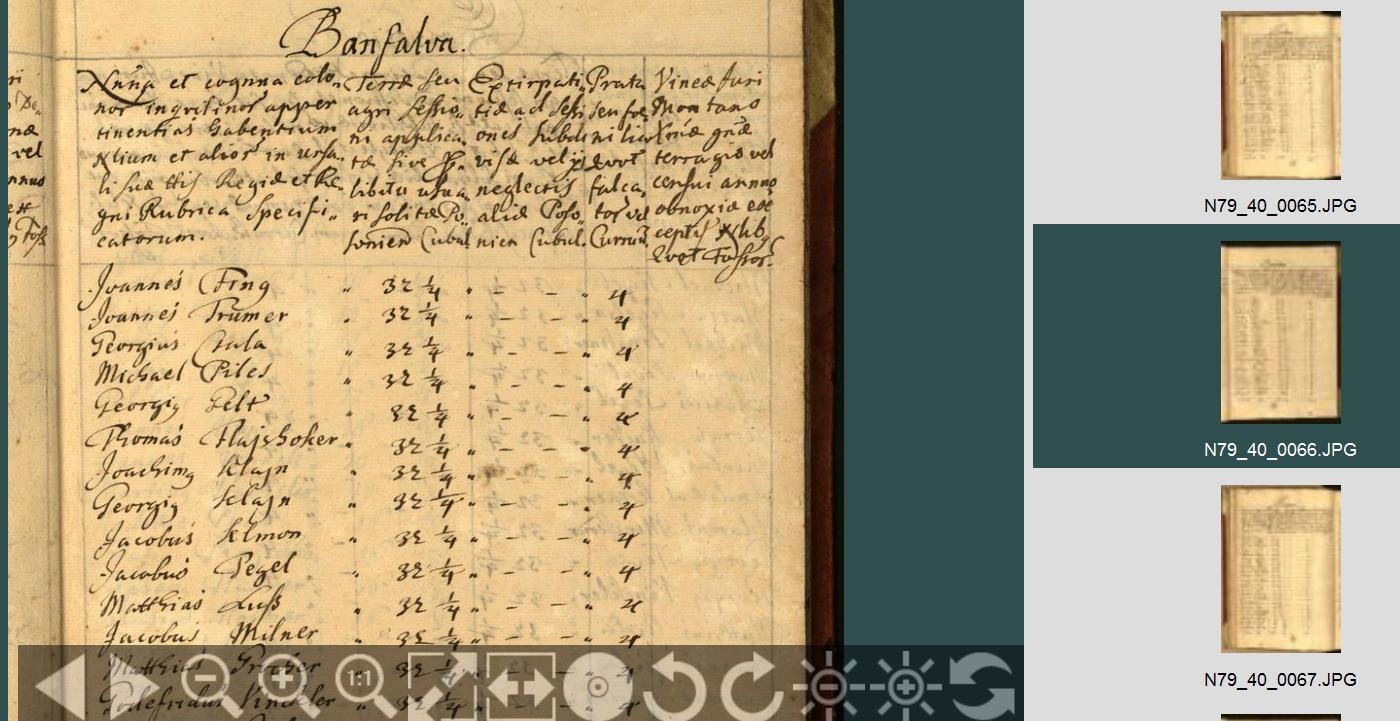

We wanted Apetlon = Bánfalu... If you check the Moson list, you will find Banfalva (remember, -falu and

-falva are interchangeable). Let's click on that name and see what its content page shows.

To

the right is a clip taken after I clicked on Banfalva. The first thing worth noting, is that the scrolling list

remains overlaid on the Banfalva page. If you move your mouse pointer into or away from the area of the scroll list,

the list will collapse to just the grey header bar or flicker back into view. This behavior can be a real nuisance, as you

can't really see or access the text underneath it (I see this as a design flaw also). However, there is a built-in

work-a-round... note the boxed "X" at the right end of the scroll list header bar? Clicking the X will remove the scroll

window, including its header, from the page (if you want it back, you can click the black vertical box on the left edge of

the page, the one with vertical text Hierarchia; alternatively, if you want the list to remain on the page and not

flicker in and out, you can click the empty box next to the X). To make exploration of the Banfalva content page

easier, I suggest you click the X. To

the right is a clip taken after I clicked on Banfalva. The first thing worth noting, is that the scrolling list

remains overlaid on the Banfalva page. If you move your mouse pointer into or away from the area of the scroll list,

the list will collapse to just the grey header bar or flicker back into view. This behavior can be a real nuisance, as you

can't really see or access the text underneath it (I see this as a design flaw also). However, there is a built-in

work-a-round... note the boxed "X" at the right end of the scroll list header bar? Clicking the X will remove the scroll

window, including its header, from the page (if you want it back, you can click the black vertical box on the left edge of

the page, the one with vertical text Hierarchia; alternatively, if you want the list to remain on the page and not

flicker in and out, you can click the empty box next to the X). To make exploration of the Banfalva content page

easier, I suggest you click the X.

Having closed the scroll window, the next thing you should do is examine the multicolored string of names that appears on

the left below the indicator of where you are in the hierarchical list (see example below):

Moson megye (40. Téka) > Alap településcsoport >

Banfalva, Bánfalva,

Mosonbánfalva, Moson, Apetlon, A

This list of names shows, from left to right: the name as it appears in the 1720 Urbár (shown in brown and

underlined); the village name given in the 1808 Lipszky Repertorium (dark blue); the 1913 village name (in green) and

the county (red) it was then located in; and the current village name (in bright blue), with a country indicator (A =

Austria), if not in Hungary. Be sure to check this list to assure yourself that you have the right village.

However, do note I have seen one instance where I believe an Urbár listing was connected to the wrong village.

Specifically, a list titled Szent Grótth was assigned to Deutsch Gerisdorf (Német-Gyirót) while I believe it should

have been assigned to Gerersdorf bei Güssing (Német-Szent-Grót). I base this belief on 1) the relationship of the list name

to the Hungarian name for Gerersdorf: Szent Grótth vs. Német-Szent-Grót, 2) the fact that there was a

different list, Geresdorff, already assigned to Deutsch Gerisdorf, and 3) a comparison of surnames in these Urbár

lists to surnames in our 1850s houselists for these villages, a comparison which clearly supports my belief.

Likewise, Richard Potetz has noted that Alsó-Strása was assigned to Oberdrosen while he believes the proper

connection is to Unterdrosen, which is now called St. Martin an der Raab. Arguments similar to what I gave for Szent

Grótth exist to support Richard's belief about Alsó-Strása.

The above comments are not intended to say I think there are significant problems in connecting Urbár lists to

current villages; rather, I think errors are rare exceptions. Nonetheless, if the surnames in the list seem unreasonable, do

verify that you haven't accessed the wrong list and then use our Houselists to see if there is a reasonable match in

surnames... if not, then there may be a connection problem.

Let's

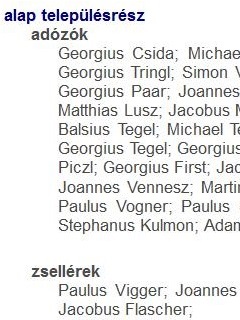

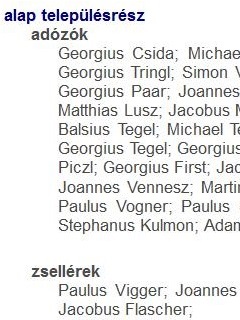

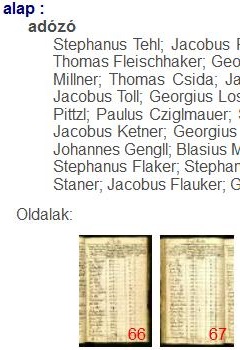

return to the Banfalva page and see what else is there. What I want to draw your attention to is the list

of head-of-household people across the bottom of the page (I show a small part of the Banfalva list to the

right). Let's

return to the Banfalva page and see what else is there. What I want to draw your attention to is the list

of head-of-household people across the bottom of the page (I show a small part of the Banfalva list to the

right).

Text alap településrész = basic settlement area while adózók = taxpayers and zsellérek =

cottars / landless peasants. For the 1720 (and 1715) Urbár, you have a complete transcription of the

names already done! This is an excellent feature that is not available for the 1767 Urbár. My perusal of the

Urbár images for several villages indicates that the transcriptions are quite accurate, so you have no need to

struggle with the old handwriting if you do not wish to do so.

This, of course, does not mean you should expect spellings of family names in the 1720 transcription to be the same as they

are now. For example, Ginger McGurk's ancestral Klein surname appears to be spelled Klajn or Klejn

in this Urbár (there are three in total but none showing in my clip).

Note: it is here that there is a slight difference between access methods for the 1720 and 1715 Urbárs. I will explain the

1720 method first then the 1715 method.

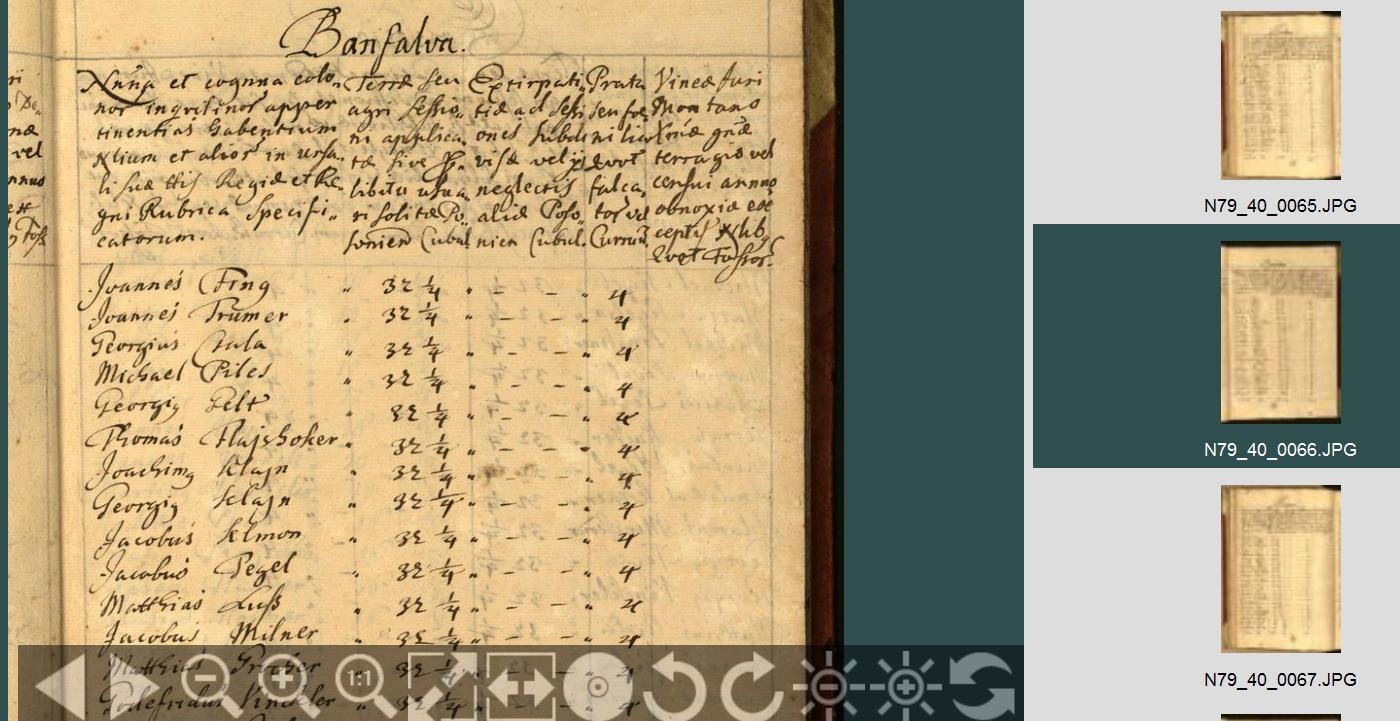

1720 Urbár method: If you want to verify the spelling for yourself or see the additional information on the

Urbár pages, all you need to do is click on the name of interest and it will open an image viewer showing

you the page on which this names appear. I'm going to do so for name Joachimus Klajn. A clip of the resulting page is

shown below, after I've zoomed in a little:

As you can see, the scanned image is shown on the left in the viewer with a scrolling selection of pages on the right. The

viewer, itself, has a bunch of clickable controls at the bottom [previous and next page; zoom out, in or 1:1; fit the page

to the viewer, whole page or page width; copy to disk (seems disabled); rotate left or right; brightness decrease or

increase; and return to defaults] and you can use your mouse to zoom (with the wheel) or drag the page about (press and hold

the left button then move).

Listed on the page are the serf's names and three columns of numerical data (at first glance, the first two columns look

like only one... but it is two separate pieces of data). The first "apparent" numerical column reports arable (plowable)

land, given in holds, and another measure of what "size" farm that is (1/2 farm, 1/4 farm, etc.). The other column

reports meadow (pasture) land, also given in holds. Joachimus Klajn is listed seventh on the page and has 32

holds of arable land, which represents a 1/4 farm, and 4 holds of meadow. Right below him is Georgius Klajn,

with the same amounts of land.

Note, however, that not all villages have two separate pieces of information in that first column. Other villages skip the