|

The

|

THE BURGENLAND BUNCH NEWS - No. 213 September 30, 2011, © 2011 by The Burgenland Bunch All rights reserved. Permission to copy excerpts granted if credit is provided. Editor: Thomas Steichen Our 15th Year. The Burgenland Bunch Newsletter is issued monthly online. It was founded by Gerald Berghold (who retired Summer 2008 and died in August 2008). |

Current Status Of The BB: * Members: 1959 * Surname Entries: 6718 * Query Board Entries: 4725 * Staff Members: 18 |

This newsletter concerns: 1) THE PRESIDENT'S CORNER 2) 1828 CENSUS TRANSCRIPTION FOR PAMHAGEN / POMOGY (by Greta Fisher) 3) BH&R HITS MILESTONE (by Frank Paukowits) 4) THE 1646 RAID ON NEUMARKT AN DER RAAB, Part 2 (by Richard Potetz) 5) THE CHURCHES OF STEGERSBACH 6) FOLLOW-UP ON RECENT ARTICLE: GRUMPERN 7) BH&R-BASED RESEARCH 8) HISTORICAL BB NEWSLETTER ARTICLES: a) REPORT OF TERRORIST ATTACK FROM BURGENLÄNDER ON SITE b) NO WORDS 9) ETHNIC EVENTS (courtesy of Bob Strauch, Kay Weber & Margaret Kaiser) 10) BURGENLAND EMIGRANT OBITUARIES (courtesy of Bob Strauch) |

1) THE PRESIDENT'S CORNER (by Tom Steichen)  Concerning

this newsletter, we present, as our featured article, the second half of a two-part

article by Richard Potetz on the 1646 Raid on Neumarkt an der Raab (see Article 4). As

noted last month, this article arose out of a email discussion between Richard and I about the

depopulation (or not) of Burgenland during the 150-year Turkish occupation of Hungary from the

1520s to the 1670s. As Richard shows, parts of present-day Burgenland (then Western Hungary)

were ravaged by war and/or beleaguered by Turkish raids. The first half of the article showed

the fluid and complex maneuverings and alliances that existed over the 120 years after the

Turkish occupation began but prior to the raid of 1646. Concerning

this newsletter, we present, as our featured article, the second half of a two-part

article by Richard Potetz on the 1646 Raid on Neumarkt an der Raab (see Article 4). As

noted last month, this article arose out of a email discussion between Richard and I about the

depopulation (or not) of Burgenland during the 150-year Turkish occupation of Hungary from the

1520s to the 1670s. As Richard shows, parts of present-day Burgenland (then Western Hungary)

were ravaged by war and/or beleaguered by Turkish raids. The first half of the article showed

the fluid and complex maneuverings and alliances that existed over the 120 years after the

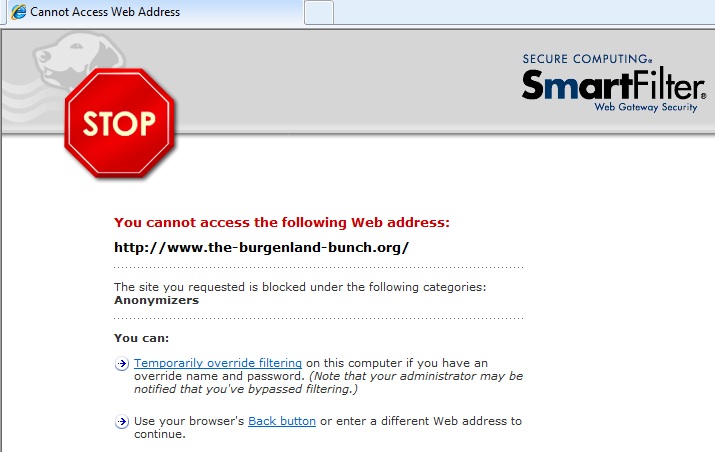

Turkish occupation began but prior to the raid of 1646. In this second half, he presents the devastation at Neumarkt an der Raab, complete with a contemporaneous letter listing the damages and the names of the victims, and then explains the aftermath of the raid. Perhaps more important, Richard raises a series of questions related to these events and provides analysis and conjecture in support of, as he calls them, guessed answers. He invites you, the reader, to join in the discussion, by raising new questions or more accurate answers, and taking him to task if he has misled himself. As always, you may reply directly to Richard or to me, the Editor. Also in this edition, we provide two articles related to BH&R (Burgenländers Honored and Remembered), one article concerning the transcription of the 1828 census for Pamhagen, another on the Catholic churches of Stegersbach, and a follow-up on a recent article. The remaining articles are our standard sections, Historical Newsletter Articles, and the Ethnic Events and Emigrant Obituaries sections. Our Historical Newsletter Articles section is dedicated to letters that were received after the 9/11 attack of 10 years ago. Member Research Editor, Barbara Raabe, recently wrote to say: As I've been merrily leading new members down the traditional path to ordering tapes [aka, microfilms] from the LDS library, I was blindsided this week when I tried to renew a tape there. Seems that as of Sep 1, 2011 the LDS libraries in the West and Northwest regions of the U.S. are only allowing you to order and reorder tapes online. The process is as follows: 1) Go to familysearch.org and sign in (located in far right-hand corner of page) to set up an account with user name, password and library location. 2) They will verify your account information by sending you an e-mail immediately. 3) Go to familysearch.org/films and put in your film number and pull down term and choose short-term or extended. Extended is like the old permanent. 4) Short term cost is now $5.50 and extended is $13.75. Pay online with bankcard, etc. 5) When the film arrives, they will notify you and, as before, you go to the library to read it. The hitch is when you are caught in the middle of the changing of the system, as I was, in attempting to renew a tape that was already at the library before it was returned. If anyone finds themselves in that state, here are the steps to follow according to Sister Butler at headquarters in Salt Lake: 1) Head librarian at your LDS library goes into the system and marks the tape returned. 2) Head librarian goes into private collection and re-enters it as a short term loan with whatever date it was supposed to be returned. 3) Head librarian does not send tape back to Salt Lake. 4) Then patron can go to familysearch.org/films and supposedly order the film as extended online. 5) Head librarian will refund the $6.25 you paid extra through this process when you go to the library. Contributing Editor Margaret Kaiser replied to Barbara saying: I'm on the East Coast and this new ordering process is not yet in effect. [She then asked] are you saying that the price will be either $5.50 or $13.75, not $5.50 plus $13.75? If so, this fee is less costly than the current fees (here $6 + $5.50 first renewal; + $5.50 second renewal/permanent, total $17 vs. $13.75). This should be a warning to all of us... on my last FHC visit in NC, the folks there told me this approach was coming but not yet available. So, be forewarned: implementation of online microfilm/microfiche ordering is now available in various locations but may or may not be required or available at your location; do check with your FHC before trying to order online. According to the FamilySearch blog, below is a list of ecclesiastical areas of the Church where the Film Ordering System is available (or will be soon): • Canada

The sooner I become aware of these types of problems, the sooner I can fix them. A message

from you may be key in keeping the BB content available to our members and visitors... but I

truly hope I never have another conversation because of this type of problem! |

2) 1828 CENSUS TRANSCRIPTION FOR PAMHAGEN / POMOGY (by Greta Fisher) Ed. Note: BB Member, Greta Fisher, of South Bend, IN, recently completed a transcription of the 1828 Hungarian census of Pomogy, Hungary—now Pamhagen, Austria—and donated it to the BB. Klaus Gerger kindly formatted the key columns of the transcription as a sortable HTML file, available at webpage http://www.the-burgenland-bunch.org/HouseList/ND/Pamhagen1828census.htm; the page also links to http://www.the-burgenland-bunch.org/HouseList/ND/Pamhagen1828_census.pdf, which is a pdf of Greta's full transcription. I asked Greta to share some background about herself and this project, which she promptly did. By the way, she also reports that she is currently working on a transcription of the 1715 census for Pomogy... so another treat may await us! Thank you, Greta, for sharing with the BB membership.  Greta

writes: In the latter half of the 19th century, South Bend, IN, was an industrial

powerhouse. It was the 7th largest manufacturing center in the nation and immigrants from

across Europe came looking for work. Pamhagen (or Pomogy, in Hungarian), was a village of

about 2,000 inhabitants in Austria-Hungary. Who knows how the first immigrants from Pamhagen

found their way to South Bend but, by the early part of the 20th century, there had been a

steady stream for decades. By the 1940’s, there were hundreds of families in South Bend that

could trace their ancestry back to this small community. My grandfather, Joseph Kölndorfer,

and his family were among these immigrants. Greta

writes: In the latter half of the 19th century, South Bend, IN, was an industrial

powerhouse. It was the 7th largest manufacturing center in the nation and immigrants from

across Europe came looking for work. Pamhagen (or Pomogy, in Hungarian), was a village of

about 2,000 inhabitants in Austria-Hungary. Who knows how the first immigrants from Pamhagen

found their way to South Bend but, by the early part of the 20th century, there had been a

steady stream for decades. By the 1940’s, there were hundreds of families in South Bend that

could trace their ancestry back to this small community. My grandfather, Joseph Kölndorfer,

and his family were among these immigrants.I have worked on family history for years but I always shied away from researching my family in Europe. I assumed it would be hard to find records and that those records would be in languages I couldn’t read. I wasn’t sure where to begin. When I finally starting to look, I discovered that the records from Pamhagen are astonishing. There are church records covering births, marriages, and deaths from 1826-1920 (in Hungarian and Latin, but not too hard to translate). There are census records that go back to the 1600’s. Many of these records have been transcribed by others or are readily available, but then I came across the 1828 land census. This census is a wonderful document. I laughed to see it mentioned in one location as of no use to genealogists because it doesn’t list all members of the household. I think it is an incredible tool for what it DOES list. By house number, the property owners of Pamhagen are shown with the annual grain yield of their farms, types and numbers of livestock, adult members of their households and their professions. Notes indicate widowers, veterans, and priests, among other things. Not only can a researcher see their family, but they can get an idea of how prosperous they were, their relationships to their neighbors and, in fact, get a clear picture of the overall life of the village.  The

census paints a vibrant picture of a small farming community. They raised grain. Most of the

inhabitants were farmers, with a pair of oxen for plowing, a horse for transportation, a cow

for milk, and sheep and pigs for wool and food. Although it would tell us if they did, it

shows that they were not engaged in wine making or producing timber. From the number of

widowers (14%), we can infer that many women died early, most in childbirth (the church

records bear this out). 17% of households consist of a male over 60 and adult children, which

shows us that many adult children remained at home as they started families, resulting in

multi-generational households. We can see the concentration of more prosperous citizens in the

center of town, moving out from the center to show bachelors and tenant farmers at the

outskirts. We know from the notes about veterans that men in the village were involved in the

Napoleonic wars. The number of different surnames is fairly small. The

census paints a vibrant picture of a small farming community. They raised grain. Most of the

inhabitants were farmers, with a pair of oxen for plowing, a horse for transportation, a cow

for milk, and sheep and pigs for wool and food. Although it would tell us if they did, it

shows that they were not engaged in wine making or producing timber. From the number of

widowers (14%), we can infer that many women died early, most in childbirth (the church

records bear this out). 17% of households consist of a male over 60 and adult children, which

shows us that many adult children remained at home as they started families, resulting in

multi-generational households. We can see the concentration of more prosperous citizens in the

center of town, moving out from the center to show bachelors and tenant farmers at the

outskirts. We know from the notes about veterans that men in the village were involved in the

Napoleonic wars. The number of different surnames is fairly small.I decided to transcribe the census for two reasons. The first is a selfish one. In 1828, so many families in Pamhagen are related to me that I thought it would make my work easier to have it all at my fingertips. The second is that I owe those who have made so many records available online a debt, and this is a way to repay it. There are other records out there and many of them are not yet available online. I hope to keep working so that Burgenland genealogists everywhere can access information about their families, and find out more about mine in the process! |

3) BH&R HITS MILESTONE (by Frank Paukowits)  This

past August, the BH&R site recorded the 10,000th person in its database of deceased

Burgenländers who immigrated to the United States. It took nearly a decade to reach that

milestone and was only achieved because of the hard work of a number of BB staff… in

particular Bob Strauch and Margaret Kaiser. This

past August, the BH&R site recorded the 10,000th person in its database of deceased

Burgenländers who immigrated to the United States. It took nearly a decade to reach that

milestone and was only achieved because of the hard work of a number of BB staff… in

particular Bob Strauch and Margaret Kaiser.The inspiration for the site was Anton Traupman, a 90-year-old immigrant, himself. Back in 2002, he visited cemeteries in the New York City area with his son-in-law, Frank Paukowits (BB member), and pointed out the places where all the Burgenländers were buried. A database of immigrant names for New York was then developed, showing the cemetery where they are buried, the names of the towns where they were born, and the years of their birth and deaths. From this initial database, the effort expanded exponentially. The site was initially conceived as a way to preserve the memory of immigrants who left their homeland in Burgenland to make a new life for themselves in America. As time has gone on and as the database has grown, it has also become a useful tool in the research being done by BB members. Currently, there are 14 specific geographical areas around the country that are represented in the combined database on the site. By far, the area with the most names is the Lehigh Valley area of Pennsylvania, which had a large influx of Burgenländers over the years. Since then, enhancements have been made that have improved the overall effectiveness of the database as a research tool. Now people can do research without going through the database page by page. Essentially, they can get to information quicker and easier. Because of the size of the database, more and more BB members doing research are looking to the BH&R site for details on their ancestors. This pattern is expected to continue in the future as additional names are added to the site. People are encouraged to look to this database as part of their genealogy tool kit when researching their family roots. Ed. Note: Frank is correct that the BH&R pages are a vital resource for Burgenland genealogical research. The BH&R database ties together names (especially often-unknown maiden names) with their spouses, birthplaces and final resting places. For a small number of families, it also includes treasured pictures. Margaret Kaiser, one of the reviewers of new BB membership applications, often shares information from the BH&R pages with the new member. We offer our thanks to Frank and his team for sharing this labor of love! |

4) THE 1646 RAID ON NEUMARKT AN DER RAAB, Part 2 (by Richard Potetz)  In

the August Burgenland Bunch Newsletter, Part 1 of this article described the background

history leading to the 1646 Raid on Neumarkt. Neumarkt was one of the villages in Herrschaft

Dobra/Neuhaus, a manor owned by Count Adam Batthyány and administered by a castellan living in

Castle Dobra. In

the August Burgenland Bunch Newsletter, Part 1 of this article described the background

history leading to the 1646 Raid on Neumarkt. Neumarkt was one of the villages in Herrschaft

Dobra/Neuhaus, a manor owned by Count Adam Batthyány and administered by a castellan living in

Castle Dobra.In 1644, Ottomans, at a fortress 50 miles away, threatened to raid Neumarkt unless tribute was paid. Following the direction of their castellan, the people of Neumarkt did not respond to the threat. Count Batthyány did increase soldiers in the area. Villages to the south and east of Neumarkt had already been threatened, with some paying tribute. Some nearby villages had been raided, with people killed, homes and farms burned and people abducted into slavery. In 1646, Neumarkt was raided. Part 2 – A Letter Lists the Damage Inflicted by the Raid Two days after the raid, Christoph Scholtz, the castellan of manor Dobra/Neuhaus wrote to his master, Count Adam Batthyány. A German translation of that letter (originally written in Hungarian), is translated to English below: 1646, 9th March. As an obedient servant, I commend myself to my gracious lord. God bless Your Grace along with all of your estates. Know Your Grace that last Wednesday morning Turks plundered Neumarkt, which I would have liked to report to Your Grace immediately. But I also wanted to look into the matter of how many prisoners they abducted. I can tell Your Grace that there are 208, mostly just women and children. About 80 were the property of Your Grace, probably all of the remaining part were the property of Madame Forgách. [Note: Madame Forgách is Adam Batthyány’s sister Barbara, the wife of Janos Sigismund Forgách, the Earl of Forgách.] Twenty-three houses were burned, and as much as we have found, six people were burned, but we can not determine exactly how many were burned or drowned. Thirteen people were killed. Also all of the livestock of the unfortunate people was burned. That is what I wanted to tell Your Grace. May God continue to grant you a life of prosperity and good health. From Neuhaus, 9 March 1646 7 March 1646: The damage done by the Turks in Neumarkt. The possessions of my gracious lord, Count Adam Batthyány: 1. Judge Gregor Neubauer's wife Margaretha, his three sons Johann, Georg and Andreas, and his two daughters Eva and Ursula, were abducted. 6 people. A horse was also taken away. Twenty Hungarian Guldens in cash. 2. Michael Pink's wife named Ursula, a son Georg, and a servant Blasius, were abducted which means: 3 people from that house. 3. A son of Georg Müller named Matthias was abducted. 1 person. 4. The wife of Matthias Bihep, named Barbara, and his two daughters Margaretha and Eva were abducted. 3 people. 5. Hans Schmied had his one son, named Hans as well, abducted. 1 person 6. Shoemaker Oswald Huber's wife Anna and two little daughters Magdalena and Susanna were abducted. He has abandoned his house. 3 people. 7. Shoemaker Stefan Steinklauber’s wife named Ursula, and both of his little daughters Susanna and Ursula, were abducted. His two journeymen were killed. His house was burned down. 5 people. 8. Lorenz Müller had a son Georg and a daughter Eva abducted. 2 people. 9. Paul Marz had three sons and three daughters abducted, namely Hans, Mathias, Adam, Eva, Veronika and Susanna. 6 people. 10. Christian Bauer’s house and farm were burned along with his horse. 11. Andreas Omasser had a son Michael and a daughter Magdalena abducted. 2 people. 12. The butcher Georg Miess was murdered, his wife abducted, his house burned down. 2 people. 13. Matthias Wagner, his wife Dorothea and his son George were abducted. 3 people. His house and farm were burned down; sixteen farm animals were also burned. 14. Michael Schwarz’s wife Veronika, son Johann, four daughters, Gertrud, Elizabeth, Anna and Ursula, were abducted. 6 people. 15. Martin Müller’s wife Ursula and his two sons Michael and Peter were abducted. 3 people 16. Sebastian Posteiner's wife Ursula and his daughter Barbara were abducted. 2 people. 17. Michael Deutsch's two daughters Gertrud and Margaretha were abducted. 2 people. 18. Blasius Taubner was beheaded, his wife abducted with a daughter Eva; his house is abandoned. 3 people. 19. Martin Scheidl was abducted with a servant and his daughter named Agnes; his house is abandoned. 3 people. 20. Christian Mex’s wife Katharina with two daughters Barbara and Ursula abducted. 3 people. 21. Peter Dinssleder was abducted. A serf living with him was killed. 2 people. 22. The wife of Hans Daucher named Agnes, his son Andreas, and his daughter Anna were abducted; his house and farm were burned down. 3 people. 23. Peter Bandl’s wife Anna, his farmhand Adam, a woman Susanne with her little daughter Barbara who lived in the house, were abducted. 4 people. 24. Peter Schreiber's wife Margaretha, his three sons, Johann, Martin, Michael and a daughter named Agnes were abducted. His house and farm, along with eight farm animals were burned. 5 people. 25. Hans Karner was beheaded. His wife Barbara, his two younger siblings, Michael and Barbara were abducted. House and farm, a child, and three farm animals were burned. 4 people. [Note: The child burned is not included in the subtotal of 4 people, but is correctly included in the summary totals at the end of the letter.] 26. The carpenter Georg Nagl with his wife Gertrud, a son Georg and a daughter Ursula were abducted. His house and farm as well as five farm animals were burned. 4 people. 27. Peter Kornhäusl’s son Michael, his daughter Eva, his farmhands Stefan and Ursula were abducted. Also two horses. 4 people. 28. Peter Kern was killed. His son Adam, his little daughter Ursula, the wife of linen weaver (Takach) Blasius name Katharina, along with her brother, both tenants in the house, were abducted. 5 people. 29. The potter Georg Bauer was beheaded; his wife Anna, his daughter Ursula, and his brother Adam were abducted. His house is burned down. 4 people. 30. Simon Hodler's two sons Michael and Georg were abducted. A tenant named Hans Großschädel was murdered; his wife Katherina was abducted with her two sons, George and Hans, and daughter Eva; this means 7 people from this house. 31. The manor farm's manager, Valentin Foltl, was abducted along with his dear son Michael. His house was burned along with the manor farm and an ox and a cow. 2 people. The total over the possessions of the gracious Master are as follows. Abducted people: 94 people. Eight were killed, one burned. Makes a total of 103 people. Burned livestock of the possessions of the gracious Master: 66 farm animals. Seven horses were led away. Makes a total of 73 head of livestock. Burned down houses in the possessions of gracious Master 14; abandoned houses: 3 Of the possessions of gracious Master, cash robbed in Hungarian Forints: 20 Possessions of the gracious Madame Forgách (wife of Sigismund Forgách and sister of Count Adam Batthyány): 1. Judge Adam Poklos’s son Georg, his two daughters, Barbara and Eva, as well as a farmhand Michael and farm maid Eva were abducted. His house and farm, and his wife with a little child, Michael, were burned, also nine farm animals. This makes from this house. 7 people. 2. Gregor Gal was killed, his daughter Mary abducted. His house is abandoned. 2 people. 3. Stefan Koh's brother Hans, his daughters, Eva and Gertrud, and his farmhand Christian were abducted. 4 people. 4. Christian Staudenbauer’s (Staindenpor) daughter Katharina, the wife of Loren Deutsch named Katharina and residing with him, their daughters Susanna and Eva, also the daughter Eva of the widow living there, were abducted. 5 people. 5. Andreas Pink was killed, his wife Magdalena abducted with his son Hans. 3 people. 6. The wife of Hans Koh and his two little daughters Ursula and Eva were abducted. His house and two farm animals were burned. 3 people. 7. Gregor Fischer was killed; his wife Margaretha and his little daughters Ursula, Magdalena, Eva and Veronika were abducted. 6 people. 8. Margaretha, wife of Andreas Müller, his two sons, Hans and Georg, as well as his farmhand Adam were abducted. His house and farm as well as five farm animals were burned. 4 people. 9. The other Andreas Müller’s two sons, Hans and Martin, and his three daughters, Ursula, Margaretha and Magdalena were abducted. His house and farm as well as five farm animals were burned. 5 people. 10. Paul Karnik’s wife Magdalena, his son Michael and his daughter Eva were abducted. 3 people. 11. Hans Schmied's wife Gertrude, his son Georg, his two daughters, Susanna and Barbara, and a farm maid Maria were abducted. Two horses were also taken away. Also fifteen Gulden cash. 5 people. 12. Bartholomäus Parin's wife named Elisabeth, his two daughters Maria and Margaretha, were abducted. Likewise, a small child, which later was lost and died on the road. 4 people 13. Gregor Pinkler’s wife named Marianna, his three sons, Gregor, Lorenz, Georg, and three daughters, Eva, Barbara, and Christina were abducted. His house and farm were burned. Also three farm animals were burned. 7 people. 14. The house and farm of the wife of Hans Marz burned down. 15. Stefan Scheidl (Sadl) was killed. His wife Katharina with her mother named Agnes, his sons Andreas, Michael and Hans, were abducted. His house is abandoned. 6 people. 16. Michael Plaizer’s wife, Ursula, his son Jacob, and his daughter Eva were abducted. His house and farm were burned down. Also, seven farm animals were burned. 3 people. 17. Peter Schwarzl’s two sons Urban and Georg, and his daughter Veronika were abducted. Also his house was burned down. 3 people. 18. Stefan Müller’s wife Anna, his son Andreas, his four daughters, Eva, Ursula, Katharina and Margaretha were abducted. His house was burned down. 6 people. 19. Georg Schmied’s three sons, Andreas, Georg, Hans, his daughter Barbara were abducted. His house was burned to the ground. 4 people. 20. Georg Müller’s wife Agatha, and his four daughters, Anna, Katharina, Eva and Susanna were abducted. Also, two horses were taken away. 5 people. 21. Ruprecht Müller’s four daughters, Eva, Gertrud, Margaretha and Susanna, as well as their mother Ursula were abducted. 5 people. 22. Hans Hozinedl’s two little daughters Eva and Susanna were abducted; from the same house, Maria, little daughter of the butcher of Neuhaus, was also abducted. What wine was there, was drained out and wasted. 3 people. 23. Hans Müller’s two little daughters Eva and Margaretha, and from the same house, Gertrud, daughter of Blasius Föbl, were abducted. 3 people. 24. Georg Mager's son Georg, and his daughter Margaretha were abducted. His house is abandoned. 2 people. 25. Hans Wagner was killed; his wife Anna, his son Michael, the daughters Elizabeth and Margarethe, were abducted. His house is abandoned. 5 people. 26. Matthias Lang's wife and his two sons Georg and Hans were abducted. 3 people. 27. The herdsman Georg Fohint's wife Margaretha and his son Jacob were abducted. His daughter named Maria burned, together with an infant. The house is burned down. 4 people. 28. The herdsman Thomas Tischler was killed; his wife Eva and his son Valentin were abducted. 3 people. 29. Two teenage boys from Jennersdorf who went to the mill wanting to grind some flour fell into the hands of the Turks; one was killed, the other abducted. 2 people. 30. A girl from Mühlgraben who was at the mill was also abducted. 1 person. Among the possessions of the gracious Madame Forgách the total of abducted people is 105. Killed were 7; four perished in the fire; one person was lost and died on the road. Makes a total of 117 people. Burned were 31 farm animals, five horses were driven off. Makes a total of 36 head of livestock. Burned down houses: 11; abandoned houses: 4 Cash stolen: 15 Hungarian Forints. From the possessions of both, 199 people were abducted; 15 were killed; the fire burned 5; one person was lost and died on the road. Makes a total of 220 people. Houses burned down total 25; 97 farm animals burned; 12 horses were driven off. Total: 109 head of livestock. Abandoned houses 7; looted cash 35 Hungarian Forints. Events after the Raid Garrisons stationed at Csákánydoroszló and Körmend in Hungary were alerted to pursue the raiders. Those towns, on the Raab River 16 and 20 miles downstream from Neumarkt, were Batthyány properties with small castles that formed the forward defense of Güssing. The pursuing force was made up of both foot soldiers and horse-mounted soldiers. In theory, pursuit made sense because the raiding party was small and slowed by cattle, stolen goods, and abducted people. But near the village of Németfalu, about half way from Neumarkt to the Fortress of Kanizsa, the pursuing soldiers were lured into a trap. A letter to Count Adam Batthyány from an eye-witness, Gyorgy Kelemen, who commanded the Körmend force, described the ambush. A single Ottoman rider was spotted and chased by the mounted soldiers. A large Ottoman force hidden by the terrain then attacked from two sides. Massacred were 58 foot-soldiers and five mounted soldiers from the Körmend garrison. Losses would have been even worse but rider Miklos Darabos spotted the trap and some mounted solders were able to flee. Neumarkt people continued to suffer after the raid. Imperial mercenaries, remnants of the on-going Thirty Years’ War, took whatever they could from the remaining Neumarkt population. Those mercenaries, in theory, answered to the Habsburg Emperor and received pay from the Habsburg Empire but, in practice, they were rarely paid and often just took what they needed from the people they were supposed to defend. Letters from the castellan tell the Count that Imperial soldiers took what little livestock the Neumarkt people owned that survived the fires. The people of Sankt Martin and Doiber were treated as badly. The castellan recognized that the soldiers were mercenaries who had to requisition supplies, but he complained to his lord the losses were so great he had difficulty getting his people to do manorial work. The castellan sent his servant Jurko to protest to the Lieutenant of the Imperial soldiers in Jennersdorf, but the soldiers had withdrawn from there. As the servant was passing though Sankt Martin on his way back to Castle Dobra, he was accosted and severely beaten by a mob. In a letter sent to Count Adam Batthyány on 22 April 1646, the castellan identifies one of the Count’s Neumarkt subjects, the son of Hans Sampl, as the main assailant along with several of his companions. The castellan goes on to explain that the people in Neumarkt had become unmanageable, blaming him for bringing on the raid by disallowing the payment of tribute, despite the order having come from the Count himself. People in Neumarkt then began paying homage to the Turks, disregarding the order not to, while at the same time asking permission through the castellan to go to the fortress and pay homage. Worse yet, other villages became involved. Letters from the castellan throughout 1646 report nearby villages receiving homage demands from the fortress: Doiber in July, Bonisdorf and Krottendorf in August, Liebau and Tauka in October. To deter Ottoman raiders, about two months after the raid, a deep trench was dug in Neumarkt, from the river to the southern hills. A letter from the castellan to the Count laments that the people built the trench too close to the mill and should have waited for advice from the Sankt Gotthárd manor castellan. (Castellan Scholtz was right; in October 1650 half the mill-dam was swept away by floods.) Context of the 1646 Raid on Neumarkt The 1646 raid on Neumarkt, although horrific to the people involved, was insignificant historically. There was no war at the time between the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg Empire. The raid was just a way to motivate villages to comply with Ottoman requests and raise revenue, perhaps to provide more income to support the Ottoman Sultan. The Sultan at the time, Ibrahim I, was known for lavish extremes—vast quantities of sable furs, amber, and so on for himself and his harem. Sultan Ibrahim’s excesses, extraordinary even for the times, led to his execution by strangulation in 1648, authorized by a fatwa from the Mufti (the Ottoman religious leader). The 1646 raid was so unimportant that it was forgotten amidst the multiple raids suffered by Neumarkt in that era. The story was only told after letters written to Adam Batthyány became available in modern times. A local history book, written in 1977, has no mention of the raid. Another local history book written in 2000 for the municipality of Sankt Martin an der Raab, which contains the village of Neumarkt, does include the story of the raid because, by 2000, the letters from the castellan were available to scholars and had been studied. Even though the raid was unimportant to history, and despite the anguish and horror surrounding that event, those of us with Burgenland roots can read about it to learn a little of our ancestors’ lives. Insight into Neumarkt a/d Raab as it was in 1646 The letter from the castellan tells us about Neumarkt in 1646 but also raises questions. From the list of destruction we learn some of the occupations in Neumarkt at the time of the raid. There are two shoemakers (Schuster), a butcher (Fleischhauer), a potter (Hafner), two local judges (Richter), a carpenter (Zimmermann), two herdsmen (Hirte), at least one linen weaver (Leinweber), and a farm manager (Verwalter). We also know there was a mill running when Neumarkt was raided. The German word “Hirte” translated here as “herdsmen” is a general term; it could apply to shepherds. The occupation “Richter”, translated here as “judge” performed the duties of a town mayor. Note that there were two judges in Neumarkt; one for the property of Count Batthyány and one for the property of Madame Forgách. Both appear to be prosperous; cash and a horse were taken from one while the other had two farmhands living at his farm. The higher status of the Neumarkt “Richters” is implied by their places on the lists, first in the possessions of the Count, and first in the possessions of Madame Forgách. The burning of the manor farm was listed in the letter. The manor farm would have been a much larger farm than any of the family farms. Inhabitants of the village were obliged to provide a certain number of days of work at the manor farm. Note that this is the only farm listing a farm manager, and also the only farm listing an ox. The letters of castellan Christoph Scholtz show his sadness for the people of Neumarkt. The list of damage names most of the children. Diminutive words for daughter and son are used several times in the list, translated to English as little daughter or son. An undertone of endearment is often communicated with these words. In another letter the castellan refers to the inhabitants left after the raid as the unfortunate people (“die armen Menschen”) of Neumarkt. Christoph Scholtz would have known at least some of the killed and abducted people quite well, certainly the manager of the manor farm with his family. Castellan Scholtz carefully identified and recorded the seven houses left abandoned by the raid. An account listing the damage done by the raid would properly draw the property owner’s attention to abandoned homes. An empty farm house produced no income and would deteriorate unless soon occupied. For two of the abandoned homes, the adult male was neither killed nor abducted, but the wife at the home was abducted. Perhaps a farm with just an adult male was not viable; the work of a wife being needed to prepare food, make soap, tend chickens, etc. The money robbed in the raid was a standard European currency at that time. Cash was reported stolen at two locations in the raid, 20 Hungarian guldens from the home of Judge Gregor Neubauer and 15 guldens from the home of Hans Schmied.  The

same money was called Hungarian forints later in the letter, but a person reading the letter

at the time would not have been confused. European commerce at that time often used gold coins

based on the Italian florin. Those coins contained 3.5 grams of gold, no matter who made them.

On the Hungarian forint, the florin’s image of St. John was re-labeled Saint Ladislaus.

Another variation of the florin was the Rheingulden, minted in the Rhine River valley, but by

1626 that coin was only 77% gold. The term “Hungarian gulden” was just another term referring

to the Hungarian forint. The value of the Hungarian forint based on today’s value of gold

would be 200 US dollars; hence the thirty-five gold coins robbed in the raid would contain

gold worth seven thousand dollars. The

same money was called Hungarian forints later in the letter, but a person reading the letter

at the time would not have been confused. European commerce at that time often used gold coins

based on the Italian florin. Those coins contained 3.5 grams of gold, no matter who made them.

On the Hungarian forint, the florin’s image of St. John was re-labeled Saint Ladislaus.

Another variation of the florin was the Rheingulden, minted in the Rhine River valley, but by

1626 that coin was only 77% gold. The term “Hungarian gulden” was just another term referring

to the Hungarian forint. The value of the Hungarian forint based on today’s value of gold

would be 200 US dollars; hence the thirty-five gold coins robbed in the raid would contain

gold worth seven thousand dollars.Wine appears to have been highly regarded in Neumarkt in 1646. The castellan’s letter only recorded gold coins, livestock, houses, people, and wine. I understand wine is still highly regarded in Neumarkt. People in Neumarkt in 1646 were prone to use the same names. The castellan’s list has two people named Andreas Müller. When the name appears the second time on the list, that person is called “the other Andreas Müller.” Also, each Andreas Müller had a son named Hans, and there was already an adult named Hans Müller in the list! Two hundred years later this tendency to name multiple people with the same name would continue in the Sankt Martin church records, forcing today’s genealogy hobbyists to follow multiple paths to verify they’re following their true ancestors. Questions and Guessed Answers Why did there appear to be two owners for Neumarkt at the time of the raid? We know from the Batthyány family history that there was really just one owner of all Batthyány property in 1646. It was not until after the death of Count Adam Batthyány in 1659 that Batthyány property came under two owners, Adam’s sons Count Christoph II Batthyány and Count Paul II Batthyány. The lord of a manor could mortgage a village or even a group of villages with the income from the mortgaged property then belonging to the mortgage holder. Perhaps that is why there is a list of damage done to the property of Adam Batthyány’s sister Madame Forgách. Another possibility is that Madame Forgách inherited lifetime income from that property. In any case, all of Neumarkt was part of the same manor, Herrschaft Dobra/Neuhaus. A manor, or even part of a manor, could only be sold with permission of the King. And only with permission of the King could a woman inherit a manor. The area considered the property of Madame Forgách was extensive. Three un-named people who were not from Neumarkt were at the mill at the time of the raid. All three were listed with the possessions of Madame Forgách. Two were teenage boys from Jennersdorf – one killed, one abducted. A girl from Mühlgraben was abducted. Jennersdorf, across the Raab River from Neumarkt, had become Batthyány property in 1620, but not part of Herrschaft Dobra/Neuhaus. Mühlgraben, six miles from the mill, was a village within Herrschaft Dobra/Neuhaus. Where were the adult males at the time of the raid? They were probably working in their fields. Neumarkt houses would have been in a protective cluster, with farm fields surrounding the village. Of the 21 people killed by the raid, 15 were slain, all males. Five women and children were killed in the fires and one small child died on the road, probably unable to keep up. The selection of those killed and those abducted shows the raiders wanted compliant people. Of the 15 slain, 14 were adult males killed at their homes and one was a teenage boy from Jennersdorf, killed at the mill. Thirty-eight wives were abducted, almost all taken with their children. No more than nine adult males were among the 199 people abducted. Two of those nine abducted adult males were taken with their wives and families. The raiders would have come quickly on horseback. The abducted people would have been tied in strings of 20 or more, led back toward Ottoman controlled territory behind the horses of the raiders. A quick departure was needed before an alarm summoned soldiers. Compliant people like mothers with their children allowed a fast getaway. The number of people killed or abducted, so carefully totaled by castellan Scholtz, raises the question, “How many people lived in Neumarkt?” Only by knowing the population at the time of the raid can we understand how badly Neumarkt was affected. An estimate of 500 adults can be made based on a census taken half a century after the raid. The canonical visit of 1697 counted 412 adults in Neumarkt (311 Catholic and 101 Protestant). In the list of 220 killed and abducted by the raid, about 70 appear to be adults. Adding 70 to the number of adults present in 1697, and adding a factor for the loss of children in the raid, puts the estimated Neumarkt adult population at the time of the raid at 500. Based upon those estimates, about one seventh of Neumarkt’s adults were killed or abducted, a sad blow to the village. Fate of those Abducted We all want to know what happened to the people abducted from Neumarkt. We can only guess. In the Burgenland Bunch Newsletter # 96 written in 2001, our founder Gerry Berghold wrote, “So many 'Burgenländers' (western Hungarians) were carried off to the Ottoman Empire during the Austro-Turkish Wars (16th-18th centuries) that white Christian slaves had little value in the slave markets of Constantinople for many years. How many Turkish branches have sprouted on our family trees? .... I wonder how many ancestors were brought up as Moslem Janissaries or carried off to Ottoman harems.” Janissaries were the Ottoman infantry, historically selected from Christians who had been taken into slavery as boys, circumcised, and converted to Islam. But, by 1646, Janissaries admitted native-born Turks to their ranks, many the sons of Janissaries. Most Ottoman slaves worked as farm or construction laborers, but there were many other possibilities. Janissary units had porters, cooks, and even a harem. Mining and fishing also employed many slaves. Slavery in the Ottoman Empire was unlike slavery in America. Slaves taken as children who showed academic talent might be educated to be engineers or civil servants. Ottoman slaves could rise to high office. For example, the commander of the Fortress of Kanizsa, Tiryaki Hasan Pasha, who out-smarted Archduke Ferdinand in 1601, had been taken into slavery as an Albanian Christian child. The experience of Andreas Grein, taken from a village 70 miles north of Neumarkt, was closer to what a typical slave could expect. Andreas Grein was abducted by Tatar raiders from his farm in Purbach am Neusiedlersee in 1640. Roped in a line with other abductees and led behind the horse of a raider, he was sold at the first Ottoman village encountered. His seven years of slavery were spent poorly fed and poorly clothed, tilling farm fields. Only with the help of a woman slave who had also been abducted from western Hungary was Andreas Grein able to escape. Upon his return to Purbach in 1647 he was in such poor condition his wife could only tell it was him by the sound of his voice. His story is remarkable in that Ottoman slaves almost never returned. A clue to the fate of one family is found in the details of the list of destruction. A carpenter was abducted along with his family: “The carpenter Georg Nagl with his wife Gertrud, son Georg, and daughter Ursula were abducted.” This is one of just two husband and wife pairs abducted. It is likely this carpenter was taken with his family to continue his occupation at a place under Ottoman control. My father, who learned his cabinet-maker trade in Neumarkt, always said that what you knew was more important than what you had, because what you knew couldn’t be taken from you. Maybe that bit of folk wisdom evolved from events like the 1646 raid. All 199 people abducted from Neumarkt may have been put to work in Hungary. Although the castellan’s letter refers to the raiders as Turks, the raiders were more likely Tatars. Crimean Tatars, descendents of Mongols, specialized in raids and capturing slaves. All Tatar males were horse-borne raiders, at least some of the time. All continuously practiced needed skills, firing a bow and wielding a scimitar while on horseback. Tatars were an integral part of the Ottoman Empire, supplying the vast number of slaves needed. The Sultan’s seven imperial galleys alone had 3,000 slave oarsmen. In 1662, Tatars took 20,000 Russian slaves. In 1688, Tatars plundered the Ukraine, returning with 60,000 slaves. Most Neumarkt slaves were likely relocated to Hungary because slaves needed in Turkey could be readily captured at a closer place. What About Ransom? A letter from the castellan written before the raid described a proposed hostage swap initiated by the Ottomans at Kanizsa to facilitate a ransom. In the summer of 1645, Countess Catharina Aurora Formantini, the first wife of Count Adam Batthyány, was asked to approve the swapping of a hostage for a captured subject. A man held in slavery in Kanizsa asked that he be allowed to substitute his child as a hostage, while he assembled a ransom that would then free his child. This request to the Countess appears to be extraordinary. Count Adam Batthyány owned manors in Güssing, Körmend, Pinkafeld, Schlaining, Rechnitz, St. Gotthárd, etc. The Güssing manor alone had seventy villages, some quite large. A lone subject would probably not have been able to get the attention of the Count, who had responsibility for thousands of people. Perhaps the person seeking permission was important or personally known to the Countess. Ottomans did make ransom requests when holding a wealthy person captive. In this case, the Ottoman leader at the Fortress of Kanizsa went further than that, promising that no harm would be done to the child, that it would not be sold or raised as a Turk, and giving a written commitment to return the child once the father paid the tribute. It is possible some people abducted by the 1646 raid were ransomed. About six weeks after the attack on Neumarkt, in a letter dated 20 April 1646, castellan Christoph Scholtz wrote to his lord that the people of Neumarkt sent a secret letter to the Ottomans at Kanizsa, a letter he believed asked about a possible ransom for the abducted people, and also how much of an homage tribute was wanted from them. The castellan went on to say he would inform his lord once the Neumarkt people got an answer. There is no mention of an answer or ransom in the later letters available to historians. Ottomans famously did ransom wealthy prisoners. Americans well remember the story of Captain John Smith, who was saved from execution by Pocahontas in Virginia in 1607. He had served the Habsburgs with distinction in the Long War and was captured in Hungary in 1602, after being wounded by Tatars. Because he was well dressed he was saved for possible ransom. Having been recently knighted by Sigismund Báthory, Captain John Smith had new armor and looked valuable. Well, the people abducted in Neumarkt in 1646 were not so well dressed. A slave was worth a lifetime of work. Few people in Neumarkt had enough money to pay their own worth. Relatives on Both Sides? When the Ottoman Empire next sent a large army to fight the Habsburg Empire, some people born in Neumarkt likely fought on both sides. In 1663, the Ottoman Empire sent an army of 120,000 people headed to take Vienna. Boys taken from Neumarkt in 1646 would have been the right age to participate on the Ottoman side, either as soldiers or as laborers. The Ottoman army included many laborers, needed to build bridges and dig under fortifications once the army reached Vienna. Because Batthyány regiments fought on the Habsburg side at the nearby Battle of Mogersdorf, Neumarkt would have provided soldiers to fight against their Ottoman relatives. What Happened Next in Neumarkt?  In

1664, Tatar auxiliaries attacked Neumarkt and nearby villages as a prelude to the battle of

Mogersdorf. A view of the adjacent little village of Alsőszölnök (Unterzeming in German) in

flames from that attack is shown here. In

1664, Tatar auxiliaries attacked Neumarkt and nearby villages as a prelude to the battle of

Mogersdorf. A view of the adjacent little village of Alsőszölnök (Unterzeming in German) in

flames from that attack is shown here.In 1683, Castle Dobra was sacked by Hapsburg forces. (The Batthyány estates had backed Hungarian insurgent Emmerich Thököly and provided forage for Ottoman forces.) In 1704, Hapsburg forces attacked Neumarkt, killing at least two people, burning 28 homes, and completely destroying the manorial mill. Etc. These are all stories for another day. Sources Books: - Chronik der Marktgemeinde St. Martin an der Raab (2000) (History of the Municipality of St. Martin on the Raab; Local history book for Sankt Martin on the Raab, see chronik.htm) - The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire (1977) by Lord Kinross - The Enemy at the Gate, Hapsburgs, Ottomans and the Battle for Europe (2008) by Andrew Wheatcroft Burgenland Bunch Newsletter Articles: - No. 143A, Lutheran Origins in Southern Burgenland, by Fritz Königshofer - No. 145, Counter Reformation in Southern Burgenland - Neuhaus, by Tom Grennes & Fritz Königshofer - No. 193, The Castle Ruin of Dobra Internet Sites: - http://www.batthyany.at: Internet site for the Batthyány family - http://www.vendvidek.com/indexe.htm: Internet site for Slovenes living in the Raab valley. Some of the material on this site references the book, A Magyarországi Szlovének, by Mukics Mária, Press Publica (2003) - http://www.imburgenland.at/gemeinden/neuhaus_am_klausenbach/ GKU_geschichte_kultur/KUB_kulturbauten/GKU_KUB_Ruine_Neuhaus.jsp: Ruins of Castle Dobra a.k.a. Castle Neuhaus - http://www.purbach.at: Internet site for Purback English Wikipedia Entries: - Long War (1593 to 1606 between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Ottoman Empire) - Stephen Bocskay (Transylvanian nobleman, fought for and then against the Habsburgs) - Treaty of Vienna 1606 (ended Hapsburg war with Steven Bocskay) - Peace of Zsitvatorok (1606 Ottoman / Habsburg treaty that ended the Long War) - Nagykanizsa (The full Hungarian name of the town holding the Fortress of Kanizsa) - Tiryaki Hasan Pasha (Ottoman commander of the Fortress of Kanizsa in 1601) - Miklós Zrínyi (Croatian and Hungarian warrior, statesman and poet) - Devshirme (Boy collection system whereby boys were taken for Ottoman service) - Janissaries (Ottoman infantry originally made up of Christians taken as boys) German Wikipedia Entries: - Neumarkt an der Raab (site of the 1646 raid) - Jennersdorf (town across the Raab River from Neumarkt) - Neuhaus am Klausenbach (site of Castle Dobra) - Ádám Batthyány (Count Adam I Batthyány, lord of Batthyány estates) Acknowledgements and Caveat: Thanks are due to the people of the Burgenland Bunch for sharing their findings over the years. If you are considering writing an article, know that Tom Steichen will help and call on Burgenland Bunch volunteers to assist. Fritz Königshofer corrected my German translation errors and explained the manor farm (Meierhof). Special thanks are owed to historian, educator and scholar, the late Josef Hochwarter, who wrote the chapter, “From the Middle Ages to the New Times,” in the local history book Chronik der Marktgemeinde St. Martin an der Raab. That chapter is the main source for this article and has a more complete account of the raid. [Editorial note: we have placed eight pages of that German-language chapter online at page chronik.htm.] Josef Hochwarter was a true expert who worked with contemporary primary sources, and he is owed gratitude by all of us interested in Burgenland history. Not all sources inspire such certainty. The story of the abduction of Andreas Grein, who returned to Purbach in 1647, is an example of uncertain history. That story has two versions. In one version, Andreas Grein was abducted as a boy and, in the second version, he was already married when he was abducted. This article selected the more credible second version of the story found in the book, The Enemy at the Gate, Hapsburgs, Ottomans and the Battle for Europe. The story of Andreas Grein was first passed down as folklore. The only contemporary evidence is a stone obelisk raised by Andreas Grein in 1647 thanking the Holy Trinity for watching over him in his captivity. The story of the 1646 Raid on Neumarkt scores well in credence because of contemporary letters. You may have ancestors involved in the raid even if you don’t match a surname in the castellan’s list. A number of people are listed without a surname. Also, some surname spellings are thought to have evolved as follows: Müller to Miller; Pink to Pint; Scheidl to Sadl; Staudenbauer to Staindenpor; Poklos to Poglitsch; possibly Daucher to Taucher. Finally, please be aware that the author of this article is not a historian or scholar, and can barely read German. Even the letters from the castellan, our trusted contemporary source, are double translated, once from the original Hungarian to German, and then to English for this article. So please accept this article as just the writing of a curious person with Burgenland roots who wants to share what he has read. And if you have a comment, question, or view on any event, tell us in the Burgenland Bunch newsletter, please! |

5) THE CHURCHES OF STEGERSBACH I recently received a request for information that caused me to discover one of the more unusual churches of Europe... the Heilig Geist Kirche (Holy Spirit Church) in Stegersbach, Burgenland. Non-member (aka, potential new member) Tom Tannehill wrote: Greetings Mr. Steichen! My name is Tom Tannehill and my wife (Tonya) and I are planning a trip to Austria this September. I am trying to surprise her by doing some research on her great grandmother Anna Mayer. We believe Anna was born in Stegersbach, Austria, on March 3, 1877. We are also relatively sure that she was Catholic. If you could possibly direct me on who to contact in Stegersbach regarding looking at church records (or something of that nature) so when we get there we can do some more research, it would be much appreciated. Stegersbach looks to have a population of around 2,500 so I can’t imagine there would be very many catholic churches! We are planning to stay about a week. My cell phone number is below if it would be more convenient for you (or just let me know when and where to call you and I will). Best Regards, Tom I replied: Tom, The Stegersbach parish info is as follows: Rom. Catholic Parish Stegersbach, Church Street 21, 7551 Stegersbach, Austria Charles Shepherd Fields, Pastor; Renate Heller, Pastoral Assistant; Anita Schittl, Secretary Telephone: +43 (0) (3326) 52 362; Fax: +43 (0) (3326) 52 362 4 Homepage: www.pfarre-stegersbach.at; E-mail: pfarramt@pfarre-stegersbach.at There is only one Catholic parish there (though they built a new church in 1974 and also kept the old one). Do note that it is not automatic that anyone will let you look at the church records, so do contact them to get their agreement and to set an appointment. While you may wish to see the original birth/baptism record in the parish, it might be good to first verify that it is really there by viewing a microfilm copy of those church records at a Mormon Family History Center (FHC). The film number is 700731 for the time period (1870-1895) you mention. Film 700730 covers 1828-1870, so you could go back a few more generations in that one (assuming the family was in Stegersbach during that period). The church itself likely has even older records. To find an FHC, go to http://www.familysearch.org/eng/library/FHC/frameset_fhc.asp and put in your location information. You’ll get a list of the nearest places. Good luck! Tom Steichen And Tom replied with his thanks: Tom – thank you so much for the quick reply and direction! Best Regards, Tom However, in the process of researching the above information, I realized how unusual the "new" church in Stegersbach was. The Heilig Geist Kirche was dedicated in 1974, after three years of construction and a prior six years of planning and fundraising. It was built to replace the classic Ägidius (St. Giles) painted plaster, square towered, Baroque church that had stood from the 1300s, but was now too small.  These

two churches stand side-by-side, with the new church on a small rise above the old one. As you

can see in the picture to the right, they could not be more dissimilar! These

two churches stand side-by-side, with the new church on a small rise above the old one. As you

can see in the picture to the right, they could not be more dissimilar!The design idea of the new church is a "spiral of God, a stairway to heaven." The church is steel-framed, with walls clad with polyester resin plates coated with marble sand, ceramic tile floors, and wood ceilings. The spiral begins at the entrance of the church then twists inward and upward, topped by a cross. Directly below the cross is the altar, which is surrounded by seating for 380 participants and slightly lowered to provide sight lines for all.  Not

surprisingly, the interior and sanctuary of the new church (picture at left) is as modern as

its exterior and is in clear contrast to those of the church it replaces (see picture below

left). Not

surprisingly, the interior and sanctuary of the new church (picture at left) is as modern as

its exterior and is in clear contrast to those of the church it replaces (see picture below

left). The Joseph's Chapel is also part of the building but separated by a glass wall; it is used for smaller weekday and private services. The parish rectory, also directly connected, provides office, meeting and living spaces for the staff. Beneath the main sanctuary are a large multipurpose room, several smaller meeting rooms, and the needed support functions.  In

addition, you will find something quite unusual by staid American standards: there is a

full-featured tavern on that lower floor, complete with food and games tables, billiards and a

bar, all designed to make the church a week-long gathering place. This completes the design

and allows the church to function as a multi-purpose community center. In

addition, you will find something quite unusual by staid American standards: there is a

full-featured tavern on that lower floor, complete with food and games tables, billiards and a

bar, all designed to make the church a week-long gathering place. This completes the design

and allows the church to function as a multi-purpose community center.For financial reasons, the new church had to make due with an electronic organ in its early years. However, in 2007, funding was adequate to order an organ worthy of the new church and, in 2008, the 1252 pipes were ceremonially dedicated and put into use for church services, recitals and other community cultural events. However, the old church was not forgotten! The opening of the new church allowed the opportunity to restore and renovate St. Giles.  Verein

"Rettet die alte Kirche von Stegersbach" (the "Save the old church of Stegersbach"

organization) carried out a five-stage comprehensive renovation (roof repair, exterior plaster

repair, exterior painting, interior restoration, and outdoor facilities) from 1980 to 1986.

The tower was renovated in 1991 and, from 1993 to 1995, the interior furnishings and artwork

were restored to their former glory. Verein

"Rettet die alte Kirche von Stegersbach" (the "Save the old church of Stegersbach"

organization) carried out a five-stage comprehensive renovation (roof repair, exterior plaster

repair, exterior painting, interior restoration, and outdoor facilities) from 1980 to 1986.

The tower was renovated in 1991 and, from 1993 to 1995, the interior furnishings and artwork

were restored to their former glory.Website http://pfarre-stegersbach.at/ has many interesting pictures and much detail on the history of the parish and the construction and renovation of the churches. If you travel to Burgenland, do visit both churches and send us a report. I'm sure it will be worth your time!  A

related note: On September 3rd, Northampton, PA, celebrated the bond of its

36-year-long relationship with Stegersbach by holding a dual wreath-laying ceremony at

Stegersbach Memorial Plaza in Northampton. The two cities formed a sister-city relationship in

1975, when Stegersbach dedicated their memorial located on Northamptonplatz in Stegersbach.

Northampton dedicated a matching memorial in Municipal Park in 1990. This year's program also

included flag-raisings and national anthems, addresses by invited speakers, and ethnic music

by the Coplay Sängerbund Chorus and the Hianz'nchor, with Joe Weber accompanying on the

button-box accordion. The ceremony was followed by a picnic and polka music in the Park

pavilion. A

related note: On September 3rd, Northampton, PA, celebrated the bond of its

36-year-long relationship with Stegersbach by holding a dual wreath-laying ceremony at

Stegersbach Memorial Plaza in Northampton. The two cities formed a sister-city relationship in

1975, when Stegersbach dedicated their memorial located on Northamptonplatz in Stegersbach.

Northampton dedicated a matching memorial in Municipal Park in 1990. This year's program also

included flag-raisings and national anthems, addresses by invited speakers, and ethnic music

by the Coplay Sängerbund Chorus and the Hianz'nchor, with Joe Weber accompanying on the

button-box accordion. The ceremony was followed by a picnic and polka music in the Park

pavilion. |

6) FOLLOW-UP ON RECENT ARTICLE: GRUMPERN In last month's newsletter, one of the Historical Articles (those from 10 years ago), spoke of strudel and left a question hanging: "...Frau Schuch soon brought two pans to the table - Herr Schuch said Grumpern strudel and I thought I was back in my grandmother's kitchen. The German word for potato is Kartoffeln or Erdapfel. To my grandparents it was always Grumpern - where did this word come from?" Editor Gerry Berghold then partially answered his own question, saying: "I thought it might have been borrowed from the Allentown Pennsylvania Dutch, who say Grumberra (Grundberren), but I've since found that Grumpern is pure Hianzisch, the local dialect of southern Burgenland." While this is correct as far as it went, it prompted BB member Wilhelm Schmidt to complete the explanation. Wilhelm writes: I didn’t see the question about the meaning of “Grumpern” answered in the last issue of the newsletter, either in the article or in the dictionary, where it is cited in the more common pronunciation “Grumpiarn.” It is the Hianzisch way of saying  “Grundbirnen,”

ground pears, similar to “Erdapfel,” earth apples. “Grundbirnen,”

ground pears, similar to “Erdapfel,” earth apples. – Marginal note: the clue lies in the hardening of the consonant. While many of the hard consonants are softened in Hianzisch, the “b” is often hardened to “p.” This is a common occurrence in old Gothic and the Middle Bavarian dialects. It occurs in the name of the village of my birth, “Pernau” (Pornoapati = abbey of Pernau), still pronounced “Bernau,” originally “Bärenau,” meaning bear meadow. I replied: Hi Wilhelm, that was an recycled article from 10 years ago… but I went back and looked at subsequent newsletters and did not see the question, of the source of this word, answered over the following months. However, I will post your explanation in the next newsletter… it may have taken us 10 years to resolve this but, thanks to you, we did! Ground pears… Earth apples… and I thought spud and tater were odd synonyms. But when you think about it, white potatoes and pears do have similarities, as do red potatoes and apples. Does this imply that the Hianzisch areas tended to plant white potatoes rather than red? |

7) BH&R-BASED RESEARCH In an editorial note to Article 3 above, I claimed that "...the BH&R pages are a vital resource for Burgenland genealogical research. The BH&R database ties together names (especially often-unknown maiden names) with their spouses, birthplaces and final resting places. Margaret Kaiser, one of the reviewers of new BB membership applications, often shares information from the BH&R pages with the new member." Below is an example where I used BH&R as a crucial link in assisting a correspondent. Heather Hunt of Findlay,

Ohio, wrote: My name is Heather Hunt. My Great Grandfather was David Schreiner. I do

not know much about him other than he married Theresa Damweber and lived in Allentown. I know

that he came to the USA in the 1880's and was born in Szentgvtherd, Hungary (per birth

certificate). Can you tell me anything more about him? He had a son, my grandfather, John

Schreiner who married Ruth Stoneback Shup. Ruth and John had three children, Carol, Nancy and

John. I am Nancy's daughter, Heather Newcomer Hunt. My grandmother Ruth just died this spring

and she did not really know much about that side of the family. Thank you! |

8) HISTORICAL BB NEWSLETTER ARTICLES Editor: This is part of our occasional series designed to recycle interesting articles from the BB Newsletters of 10 years ago. This month, we provide a few letters that were received by the BB after the 9/11 attacks on New York City and Washington, DC. THE BURGENLAND BUNCH NEWS No. 99 September 30, 2001 REPORT OF TERRORIST ATTACK FROM BURGENLÄNDER ON SITE (from John Gibiser Lostys) Dear Mr. Berghold, Thank you all your work with the Burgenland Newsletter. I have just written a report (below) of my experience at the WTC yesterday for ORF (the Austrian Radio Network) in Burgenland. Feel free to publish it. My Grandparents came from Wallendorf, near Heiligenkreuz, south of Güssing. I have been there many times. We spoke once. My great grandmother worked in the same cigar factor as yours in Szentgotthárd. Servus, John Gibiser Lostys Yesterday was a very long and lucky day. I work out at the gym on the 22nd floor of the Marriot Hotel, attached to the World Trade Center. I was there from 7:00 to 8:00. At the end of my workout, I went for a swim in the pool that had a great view of the WTC on one side and of New Jersey on the other side. The pool was usually crowded but, for some reason, I was the only one in it that morning. The sunlight was flowing in from the WTC side and lit up the center of the pool as I did my laps. It was so beautiful and peaceful in the water. Little did I know I was going to be one of the last people ever in the pool and the gym. There was also a wonderful young Hispanic girl, Rosana, at the desk who just started last month. She just got out of high school last spring and it was her first full time job. She was very happy with the position. Rosana was extremely friendly and polite to the clients and coworkers. On the way to the gym that morning, I bought a coffee for myself and one for her (with milk and two sugars, the way she likes it). That also brought a smile on her face. I don't know what happened to Rosana. I only hope she got out in time. At 8, I took the elevator to the lobby. There was a large convention getting started on the main floor. The day before, I had seen the convention on the national news. I popped my head into one of the ballrooms - all decked out for a fancy breakfast - but then thought I should not waste time and I should be getting to work. I then walked out of the hotel, through the WTC main floor, and down the two escalator to the PATH train to Newark (like I did every work day). So I missed the bombing by 50 minutes. Gott sei dank! My guardian angel was working overtime that Tuesday.  In

Newark, New Jersey, we saw it on the TV on the fourth floor. It looked like a movie or video

game at first. I could not believe it. Later we were able to go to the 10th floor and see the

flames and smoke on the horizon. We saw one building collapse, and then the second, before our

eyes. One coworker (Ace Romer) had a sister, who died last month, and a girlfriend who worked

in the WTC. He was trying to get her on the phone but could not get through. In

Newark, New Jersey, we saw it on the TV on the fourth floor. It looked like a movie or video

game at first. I could not believe it. Later we were able to go to the 10th floor and see the

flames and smoke on the horizon. We saw one building collapse, and then the second, before our

eyes. One coworker (Ace Romer) had a sister, who died last month, and a girlfriend who worked

in the WTC. He was trying to get her on the phone but could not get through.Another coworker, Brian, had worked with four people who left our company last year and moved to a firm at the WTC. He was awaiting a response to his calls and e-mails but with no luck. A third worker had a mother and sister who worked in the area. After three hours of people glued to the TV set, getting more upset, they called off work. The FBI also has an office in the same complex so, for safety reasons, we left quickly. The manager, Ajay, was heading to London that morning. He was waiting for a 10 o'clock flight and had checked in and was having a coffee in the lounge at Newark Airport when he saw the first blast on TV. He left and went to the check-in counter and asked about getting his baggage back. They said it was impossible. He said the hell with the luggage and left. He luckily got a taxi before the mad dash to leave the airport started. There was no way I could cross the Hudson River from New Jersey to Manhattan and cross Manhattan to Queens to get home. So the manager gave me a ride to a friend's home in a nearby town. I had to wait on the lawn until my friend and his wife got home, but I was happy to be in such a safe spot. My friend's daughter, Jena, had a teacher whose husband was in the WTC. In the town of Maplewood there is a nearby mountain. An hour before dusk, we drove up to the mountain. Most of the town was there. There were so many parked cars around. We walked up the last part of the trail and there was a beautiful crescent road on top. On the back of the crescent were green trees and on the other side was a vista of New York City, with smoke still pouring out where the WTC and the pool was that morning. Someone heard on the radio, that WTC 7, with 42 floors, was collapsing. An old woman was leaving the peak, and started to sing an old hymn as she was leaving. The song caught me and went right though me. There were no planes in the air that day, even though we were not too far from Newark airport. When one came by, everyone stopped and stared and one father hugged his son until we saw that it was a military aircraft. Before that day, we never gave a second thought about planes. We all had lost our innocence. As the sun was setting, the sideways angle of the sun was lighting up some skyscrapers and some people thought other buildings were on fire. Someone said it was just the sunlight. When we saw no smoke from those buildings, we were relieved. Everyone was shocked and saddened and nervous. People had already placed poems and messages for lost ones on pieces of paper and taped them to the rocks. I never saw such touching poems. Tears were in many peoples faces. This morning, I went back up the hill and a handful of people where there and smoke was still coming from the site. Later I took the train to Manhattan. The train was almost empty, they did not bother collecting tickets, and a woman across from me was crying quietly. I looked at her understandably but could not say anything. She just wanted to get through the new day in her own way, like I and every one else did. In Manhattan, the streets were empty in Greenwich Village. A few people were walking sadly on the street. No cars were around. One could hear a helicopter or a police vehicle in the background. I walked to Houston Street but not further. They would only let people who lived in the area and had identification below Houston. There was still some smoke coming from the site. My Catholic Church is by the Holland Tunnel, south of Houston Street, and I wanted to visit the church, but the police had more important work and I did not want to bother them so I headed back to Queens and home. I wonder if the stained-glass windows are still in the church. They were only a kilometer from the blast and faced the WTC. The priest there, Father Euguene, was the only priest who had a full time job in NYC, until last year when he retired. He was a fireman and handled the incoming calls. His father was a fireman too and had died in a fire. I wonder if he went out to help and what happened to him. NO WORDS (from Hannes Graf, Fritz Königshofer & Laszlo Apathy) Dear all, I have no words to say how I feel at this time. I see on TV what happened today in New York and Washington. I don't know, if you or your children are involved in it. I hope nobody is a victim. Hannes. Fritz Königshofer replied to Hannes: Thanks for thinking of us here in the US. As you know, I work at the World Bank in downtown Washington. My building (though not my office) has an excellent view of the Potomac River, the National Airport and the Pentagon, which lies next to this airport. I am sure many of my colleagues must have seen the incredible crash as it happened. I myself was supposed to fly to Europe on business this afternoon. Therefore, I did not go to work. Before I started packing my luggage, I received an e-mail from our daughter in London, informing me of the World Trade Center tragedy (at that time only the very first event of it). Then our daughter called me and, soon afterwards, our son (who studies on the West Coast) when the towers had already collapsed. From then onwards, I watched TV myself, but with the most awful feelings, like I am sure all of you. We are all fine, and I hope I'll not travel for the next weeks! How close it was for some families is demonstrated by the e-mail I am attaching which came from an occasional correspondence partner in Hungarian genealogy, Laszlo Apathy. Laszlo writes: Dear family & friends, Just wanted to let you know that our daughter, Christina, who lives in NYC and works at the World Trade Center, is shaken up but A-OK. Christina did NOT go to work at 9 am this morning because she had a doctor's appointment. Because she lives on the top floor of a 7-story apartment building only about 15 blocks away from the WTC, she heard the 1st airplane just go over her roof and then immediately followed by the big explosion. Christina then ran up to the roof and saw her workplace on fire. We thank Almighty God that she is safe. Please pray for all the families involved with this national tragedy. Love & peace, Laszlö & Monika |

9) ETHNIC EVENTS LEHIGH VALLEY, PA (courtesy of Bob Strauch) Saturday, Oct 8: Weinlesefest/Grape Dance. Coplay Sängerbund. Music by the Emil Schanta Band and the Hianz'nchor. Open to members and accompanied their guests. Sunday, Oct 9: Grape Dance. Ss. Peter & Paul Society ("Hungarian Hall") in Northampton. Saturday, Oct 22: Lehigh Sängerbund Oktoberfest. At the Knights of Columbus in Allentown. Info: www.lehighsaengerbund.org. LANCASTER, PA Saturday, Oct 22: Weinlesefest. Lancaster Liederkranz, 722 S. Chiques Rd, Manheim, PA. Info: www.lancasterliederkranz.com. First Tuesdays, Oct 4, 5:30-7:30 pm: All you can eat Buffet. Lancaster Liederkranz. Entertainment by Carl Heidlauf on Piano. ~ Open to the Public ~ $10 ($12 guests). NEW BRITAIN, CT (courtesy of Margaret Kaiser) Friday, Oct 7, 7 pm: First Friday. Austrian Donau Club, 545 Arch Street, New Britain, CT, (860) 223-9401. http://www.austriandonauclub.com/ Music by Joe Rogers and his band. Kitchen special: Wursts. Sunday, Oct 9, 8 am - Noon: Sonntag Frühstuck. Austrian Donau Club. Friday, Oct 21, 7:30 pm: Heurigan Abend. $3. Austrian Donau Club. Music by Schachtelgebirger Musikanten. Kitchen special: Hungarian Goulash. Friday - Sep 30, 7 - 10 pm: Gemütlicher Abend. Austrian Donau Club. Featuring Nick Kwas. Kitchen special: Sandwiches. Tuesdays at 7 pm: Men's and Women's Singing Societies meet. Austrian Donau Club. Thursdays at 7 pm: Alpenland Tänzer (Alpine Country Dancers) meet. Austrian Donau Club. ST. LOUIS, MO (courtesy of Kay Weber) Saturday, October 22: Tracking Pennsylvania Ancestors, Keys to Successful Research. Presented by the St. Louis Genealogical Society and held at Orlando Gardens, 8352 Watson Road, Webster Groves, MO. Featuring Kay Haviland Freilich, CG, CGL, Author, Instructor, Lecturer. For more information or to register, see www.stlgs.org. |

10) BURGENLAND EMIGRANT OBITUARIES (courtesy of Bob Strauch) Stefan Bendekovits  Stefan

Bendekovits, 88, of Northampton died peacefully on Wednesday, September 21 in the home of his

daughter Emilie and son-in-law George F. Martin Jr., of Roseto. Stefan

Bendekovits, 88, of Northampton died peacefully on Wednesday, September 21 in the home of his

daughter Emilie and son-in-law George F. Martin Jr., of Roseto.Stefan and his wife Emilie (Stubits) Bendekovits celebrated 59 years of marriage on February 11. Born June 4, 1923 in Northampton (and raised in St. Kathrein im Burgenland), he was the son of the late Michael and Rosa (Palkovits) Bendekovits. Stefan retired from Cross Country Clothes in 1985 after 28 years of employment. He was a member of Queenship of Mary Church and the Holy Name Society. Survivors: Besides his wife; daughters, Emilie, wife of George F. Martin Jr., of Roseto, Christine Bendekovits, of Life Path in Bethlehem; two grandchildren, Philip Martin his wife Laura, and Kristal Martin; sister, Maria Knopf of Austria; and nieces and nephews. Stefan was predeceased by 2 sisters, Rosa Rohde and Anna Dirnbeck and two brothers, Michael and Joseph Bendekovits. Services: A Funeral Mass will be celebrated on Monday, September 26 at 1 p.m. in Queenship of Mary Church 1324 Newport Ave. Northampton. Family and friends may call Sunday, 6 to 8 p.m. and Monday 12 to 12:30 p.m. in the Reichel Funeral Home 326 E. 21st St., Northampton. Contributions: In lieu of flowers, memorials may be presented to Life Path c/o funeral home. Published in Morning Call on September 23, 2011 Frank Schrey  Frank

Schrey, 81, died on Saturday, September 24, 2011 at his home in Neshanic Station, New Jersey,

surrounded by loved ones. Frank